|

After almost a year of speculation and discussions based, primarily, on rumours, the long-awaited questionnaire on the future of connectivity in Europe got leaked yesterday. Bloomberg reported it first, confirming that the controversial ‘fair share’ proposal had made it into the final draft. A leaked version of the questionnaire also made it into my inbox. Here’s a quick takeaway as I continue to absorb the minutiae of this whole initiative.

The European Commission’s Questionnaire – at least in its current form – is divided into four sections. (Until the European Commission officially launches its consultation, we should operate on the assumption that the questions and format might change).

Rather predictably, the European Commission insists on having a conversation about “fair share”. In the Questionnaire, the European Commission acknowledges that there is a great amount of division between stakeholders regarding the need for such a scheme, though admittedly it fails to reflect the difference in volume when it comes to these views (as the majority have come against any proposition for a fair scheme). To this end, instead of killing this proposal, the European Commission proceeds with presenting a problem that never actually existed. Seeking to appease experts as well as civil society and other organisations that expressed concerns over the future of network neutrality protections in Europe, the questionnaire is fast to ensure that the open and neutral Internet will be preserved according to the Open Internet Access Regulation (EU) 2015/2120; it fails, however, to point out how this will be done. The Questionnaire is silent on the most probable scenario: should a “fair share” scheme go forward, how will it deal with a potentially unruly Content Application Provider (CAP)? What other means beyond blocking or degrading the CAP’s traffic would a telecommunication’s provider have at their disposal? From the Questionnaire it becomes clear that issues of 5G development, the metaverse and cloud computing constitute core components towards ensuring a more competitive Europe in the years to come. The European Commission is right in putting emphasis on these technologies, especially considering the current geopolitical shifts and the way 5G, in particular, has become central to the way Europe has reordered and reorganised its relationships with international partners. To this end, the European Commission rightly underscores the interdependencies in its critical infrastructure and the potential vulnerabilities that these create for existing and future technologies. All this is quite fair and clear. What is unclear, however, is how a ‘fair share’ contribution will alleviate any of these dependencies. On the contrary, one would think that it could further exacerbate them. Moreover, it is also rather confusing the way the Questionnaire seeks to address security concerns and the nexus it seeks to create between them and infrastructure. Is the European Commission suggesting that, without proper financial support, all these new systems would end up being not secure? Is the European Commission implying that the security of the European infrastructure is dependent on foreign investment? I would think not. The language, however, in the Questionnaire seems to suggest that Europe’s security will be – to a large extent – contingent on the availability of financial support. “In light of this, additional needs and increased cost for strengthening the cybersecurity, and the resilience and redundancy of networks might be triggered”. Moreover, and in somewhat a disappointing way, the Questionnaire fails to reflect on the significant consumer protection issues that were previously raised by various bodies, especially the European Consumer Organization (BEUC). In its preliminary assessment back in September 2022, BEUC mentioned that “establishing measures” emanating from a fair share rationale, “would range from a potential distortion of competition on the telecom market, negatively impacting the diversity of products, prices and performance, to the potential impacts on net neutrality, which could undermine the open and free access to Internet as consumers know it today.” The European Commission should have been careful in pointing to these concerns and make them part of its public consultation. Although there is a whole section dedicated to consumer fairness, this section provides more of an account of the successes Europe has achieved in creating an affordable environment for consumers over the years rather than an exploration of how consumers may be impacted - negatively or positively - from any change in the interconnection market. Unfortunately, the whole consumer section appears to be a build-up to a worrying warning - that European consumers should be prepared to bear some costs from a change in Europe’s consumer market. “The current economic conjecture, the rising inflation and cost of energy for the businesses, and some of the technological and market developments [...] are likely to lead upwards pressure on costs for consumers at least in the short term”. It is true that Europe is suffering both from rising inflation and energy costs and that both could end up affecting consumers. Therefore, it really begs the question why the Commission would want to add more financial pressure on consumers by seeking to upend the whole interconnection market, through a “fair share” proposal. And, there is no question that this is what will happen given the experience from the South Korean market. Finally, the most obvious question missing from the European Commission’s questionnaire, and one that many others have asked, is why it is so keen to intervene in the absence of a market failure. Is it the cost of regulation? Is it the strict merger policy in the EU telecoms area (for national mergers, not cross-border mergers)? Is it a lack of innovation-mindness? Or, is there an effective market failure problem? I don’t think that anyone would be against regulation that aims to address market failures, but we should question any attempt that seeks to create the conditions for such regulation to exist. It’s easy to see how the European Commission has opted to address this highly controversial issue. Right at the start of the Questionnaire, it sets the tone of how one should proceed reading it. “The growing requirements for strategic autonomy, security and sovereignty regarding key enabling technologies in the electronic communications area will also have a significant impact on future developments”. The European Commission continues to be riding on the undefined, vague and potentially problematic for the global and open Internet notion of digital sovereignty. For anyone following European digital policy, this language is not unfamiliar; after all, digital sovereignty has defined much of Europe’s digital agenda in recent years. The idea that Europe should be able to determine its own technological future, act autonomously and cut itself from foreign dependencies has been a key driver for most of its major legislative proposals; to an extent, this idea has also legitimised the European Commission’s hard stance on many issues, from content moderation to competition and Artificial Intelligence (AI). There was no reason to think that discussions on infrastructure and the future of connectivity would be any different. However, it should be noted that Europe’s digital sovereignty approach has also raised significant concerns about its contributing role on Internet fragmentation. At first read, the Questionnaire seems messy and sounds more like an industrial policy document rather than a real attempt at understanding how investment and innovation should take place within Europe. It is disappointing to see the European Commission condensing so many different and important things in one questionnaire under such a politically-loaded environment. Discussion about the future of Europe’s infrastructure and connectivity are crucial for Europe and should take place; however, they must be detached from any attempt that seeks to pit actors against one another, especially when all of them are contributing in different ways to the Internet’s value chain. To say that Europe is about to undertake its biggest bet on the open internet is an understatement. And, unfortunately, it will lose it.

For anyone living under some cave all this time, back in March, Breton hinted that the Commission was working on a proposal requiring technology companies to contribute financially to telcos’ infrastructure costs. Since then, a series of reports that have been prepared on behalf of EU telcos have suggested this “fair contribution” to take the form of the “Sending-Party-Network-Pays” model, which has persisted their lobbying efforts since 2012. It is based on a simple premise: hand back the termination monopoly power to European telco champions. Reaction to this has been swift from across the board: civil society, European regulators, mobile virtual network operators, technology companies and more than 30 experts and academics have objected, stating that there is no clear policy objective to reopen this particular debate. Yet, the Commission persists and it appears determined to proceed with some proposal. In their response to the letter sent by more than 50 MEPs questioning this very reason for reopening the network neutrality debate, Commissioners Vestager and Bretton responded that this is not their intention: “the Commission is strongly committed to protecting a neutral and open internet, where content, services, and applications are not unjustifiably blocked or degraded in Europe, as well as on the global stage”. The SPNP model cannot ensure this and the Commission can insist as much as it wants but the fact of the matter is that once you recognize a termination monopoly right to the largest telco providers in Europe, all bets are off. As usual, the Commission wants both ways, but it is impossible. It is as impossible as its position on CSAM and encryption: we strongly believe in encryption but we ask companies to break it when we need it. This is not how things work. The letter goes on to clarify that “any interpretation of the Commission’s work suggesting that we might be in the process of reversing this fundamental principle is completely misguided”. The Commission though provides zero insight on how then this whole thing would work. The only model that is on the table is the SPNP and we know how this story ends. The model will seek to make the internet look like more like a telephone network, the internet will persist, further regulation will be required, the market will become anticompetitive and Europe will be left behind. All the while, European users and consumers will suffer. There is a sentence in the letter that “the issue of the digital players’ contribution to network deployment does not need to approached […] from the perspective of network neutrality. Again, though, no information is provided. How is it possible to talk about changing the way interconnection works in the internet and not talk about network neutrality? How is it possible to consider allowing commercial transactions to replace years of peering arrangements in the internet and not talk about network neutrality? Pretty simple, you cannot. I don’t believe anyone is against having a conversation about the way the infrastructure ecosystem can be enhanced and strengthened. This conversation though cannot start with regulation; it cannot start with a model that has already been rejected. The only way to have a rational conversation about any of this is to go back to the drawing board, define the problem, lay out the framework, conduct a cost-benefit analysis and then proceed. What saddens me is that once again the Commission fails to have an informed discussion and be transparent about any of this. To someone who was involved in the same discussions back in 2012 and then in 2015, this whole thing does not make sense. Yet, it is where we are. A Commission committed to satisfy the wishes of handful of legacy telelcom operators at my, and your, expense. Why else are they planning to open the consultation on December 21st – four days before Christmas? Here's the letter. Dear Commissioner Vestager,

Dear Commissioner Breton, The undersigned experts write to express our concern and to urge the Commission to abandon its plans to require content providers to pay telecommunication providers an "infrastructure fee", often referred to as the "Sending-Party-Network- Pays" model. Such fees violate the net neutrality rules enshrined in the 2015 Open Internet Regulation and are explicitly prohibited by every strong net neutrality regime in the world. The current use of the transit and peering model allows for competitive markets. Adopting the “Sending-Party-Network-Pays” model will upend decades of European Union policy and harm Europe’s digital agenda rather than promoting its sound commitment to openness. Proposals to charge content providers for access to broadband subscribers are not new and have consistently been rejected as harmful. In 2012, large European telecommunications operators tried to push a similar proposal at the International Telecommunications Union (ITU). This proposal was rejected by governments, experts, businesses, and civil society. Nothing has changed in the past decade that would warrant revisiting such a policy. However, large telecommunication providers have continued to lobby for a “Sending-Party-Network-Pays” proposal, instead of investing in innovation and new services. The ideas behind this proposal represent a fundamental misunderstanding of the structure of the internet. First, just like prior proposals, this proposal is based on the mistaken assumption that content providers are causing traffic on broadband networks. Broadband users are requesting this traffic, and they already pay their broadband providers to deliver this traffic to them. Forcing content providers to pay broadband providers for delivering this traffic to their subscribers just results in broadband providers getting paid twice for the same service. Second, the internet consists of more than the broadband networks that connect users to the rest of the internet. Universities, member-state governments, multi- nationals and even the European Commission all operate their own networks, independently of incumbent telecom operators. The desired rule change would break the competitive market for transit and peering. Indeed, every ISP in the EU could demand the European Commission to pay the ISP each time the regulatory department reads the EU Telecomcode. While broadband networks are an important part of the internet’s value chain, so are content providers whose services drive Europeans’ demand for broadband access. Broadband providers receive substantial benefits at no charge from content providers’ efforts to create content that broadband subscribers want. Universities, public broadcasters and governments are content providers too. All these actors already invest heavily in internet infrastructure. They pay internet service providers to transport their traffic to broadband access networks and pay content delivery networks to store their content close to the end users; many content providers even perform these services themselves. In addition, such access fees violate the Open Internet Regulation. In 2015, Europe granted end users the right to be “free to access and distribute information and content, use and provide applications and services of their choice.” The Regulation requires broadband providers to treat data in a non-discriminatory fashion, no matter what it contains, which application transmits the data, where it originates and where it ends. Charging some content providers for access to the network but not others violates the spirit and the letter of the Open Internet Regulation. Lastly, charging access fees is unlikely to solve the broadband deployment problem. History and economic theory clearly show that similar fees do not increase investment in infrastructure from telecoms. In addition, there are bigger barriers to deployment than lack of funding such as permitting and construction capacity. The war in Ukraine showed that the country's decision to move from a highly centralised Internet to a decentralised one with interconnection points in 19 cities, made it much more resilient to DDOS, fiber cuts and bombing of datacenters. The proposal for "Sending-Party-Network-Pays" would make Europe more vulnerable to attacks. We ask that the Commission not move forward with a proposal to drastically undermine Net Neutrality in Europe and the world. At this moment, Europe is experiencing a positive regulatory momentum and has become a global regulatory force. Europe should continue to lead by example, and adopting this proposal will have severe consequences both here and worldwide. Sincerely Yours, Dr. Konstantinos Komaitis, Internet policy expert Dr. Luca Belli, Professor at FGV Law School, former Council of Europe Net Neutrality Expert Dr. Niels ten Oever, Postdoctoral Researcher at University of Amsterdam Dr. Francesca Musiani, Associate Research Professor at CNRS, France, Deputy Director, Centre for Internet and Society Dr. Joan Barata, Cyber Policy Center, Stanford Raghav Mendiratta, Future of Free Speech Project, Justitia and Columbia University, New York Dr. Farzaneh Badiei, Digital Medusa Dr. Tito Rendas, Executive Dean, Católica Global School of Law Nikhil Pahwa, co-founder, SaveTheInternet.in Thomas Lohninger, co-founder, SaveTheInternet.eu Prateek Waghre, Policy Director, Internet Freedom Foundation Dr. Yong Liu, Associate Research Fellow at Hebei Academy of Social Sciences Prof. Maria Michalis, Deputy Director of the Communication and Media Research Institute (CAMRI), University of Westminster, London Dr. Nuno Garcia, Chair of the Executive Committee of the Law Enforcement, Public Safety and National Security Laboratory - BSAFE Lab, University of Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal Alec Muffett, Internet security consultant Prof. Ross Anderson, Professor of Security Engineering, Cambridge University and Edinburgh University Bogomil Shopov, civil initiative Electronic Frontier Bulgaria Marvin Cheung, Co-Director, Center for Global Agenda (CGA) at Unbuilt Labs Jonathan Care, Board Advisor, Lionfish Tech Advisors Karl Bode, Telecom analyst, writer, and editor Christian de Larrinaga, Internet public service, Investor and founder. Kyung Sin Park, Professor, Korea University Law School, Director, Open Net Dr. Ian Brown, Visiting Professor at FGV Law School Bogdan Manolea, Executive Director, ApTI, Romania Linnar Viik, co-founder, e-Governance Academy, Tartu University, Estonia Dr. Niels Ole Finnemann, professor emeritus, Department of Communications, University of Copenhagen. Denmark. Bill Woodcock, Executive Director, Packet Clearing House Moez Chakchouk, Director of Policy and Government Affairs, Packet Clearing House. Former ADG/CI UNESCO & former Minister in Tunisia Desiree Miloshevic, Internet Governace Expert Dr. Mikołaj Barczentewicz, Senior Lecturer in Law and Research Director of the Surrey Law and Technology Hub, University of Surrey Prof. Wolfgang Kleinwächter, European Summer School on Internet Governance, former ICANN Board Member. Thomas F. Ruddy, Retired Researcher, ETH Network Jaromir Novak, regulatory expert & former chairman of the Council of the Czech Telecommunication Office Note: if you are interested in signing on to the letter please email me at : konstantinos at komaitis dot org The European Commission's response to the letter is attached. reply_to_letter_of_5_october_2022_from_29_experts_and_academics.pdf On December 26, 1995, the Turkish cargo vessel “Figen Akat” ran aground on the easternmost point of the two islets of Imia, just seven kilometers off the coast of Bodrum, Turkey. When a Greek tugboat approached to help, the Turkish captain insisted that the tug was in his country’s territorial waters. After the disabled vessel made it back to its harbor, the Greek skipper put forward a salvage claim, which would signal the beginning of one of the most heated east Mediterranean crises in recent history. On December 27, 1995, the Turkish government declared the islets Turkish territory, something which Athens denied citing international law. In January 1996, two Greeks sailed off the nearby island of Kalymnos and raised the Greek flag on Imia. The Turks reciprocated. Neither country was backing down and military was now getting deployed on both sides across the Turkish-Greek borders. By the time a helicopter carrying three Greek soldiers crashed, the issue had become a NATO and European emergency.

At the time, there were rumors that we were at the brink of war. In remote places, like the island of Lesbos, things were particularly alarming. (Lesbos is the third largest island in Greece and its north coast between Skala Sikamineas and Molyvos has the shortest distance of 12 km to Turkey). People were panic-buying food and soon supermarket shelves were empty; others were fleeing the island (my older sister was studying in Thessaloniki at the time, and she called in tears asking us to go there). The island was going into frequent blackouts, apparently in order not to be visible to the opposite Turkish side and as the army was taking key positions across the island. Growing up in an island like Lesbos there is one thing you learn and that is how to live with a bad neighbor. You know the kind of neighbor that makes too much noise, does not like to work with you on almost anything, he tries to trick you and, most importantly, does not respect you. That’s Turkey for people in Lesbos and, before you all rush to accuse me of being biased, let me just say: of course, I am biased. I am Greek and we are taught early on to be biased. But, this is not about the country or the Turkish people or even about history. It is about a continuous political aggression and the constant challenge of having to defend your own identity. It is frankly exhausting. Greece’s relationship with Turkey goes through waves. Over the years, the two countries have majorly learned to tolerate one another and, overall, be courteous. In times of natural disasters humanity also prevails. When the big earthquake struck Turkey in 1999, Greece sent immediately helicopters and firefighters to help. (I remember distinctly that earthquake; it was August and, it was so strong that we also felt it in Lesbos). But, the truth is that when it comes to politics, Greece and Turkey cannot see eye to eye and most likely they never will. During Greece’s financial crisis, a lot of its foreign policy was put in the backseat. In reflection, I am sure everyone would agree it was a mistake because it allowed Turkey to elevate itself as a more reliable partner in the region while making Greece look weak. The timing of the refugee crisis and Turkey’s role created a web of dependencies on Turkey and gave President Erdogan political leverage and an excuse to often act like a sultan (in fact, he has maintained much of this behavior to this day). At the time, the European Union, NATO and, even the US, were paying more attention to Turkey than to Greece. In the last couple of years, however, Greece has become stronger. The new government has made foreign policy a priority and has managed to place the country at the center of geopolitical relevance. Greece has managed to strike strategic geopolitical deals with Egypt, Libya and Israel, it has reached out to the Middle East and has successfully convinced its international partners that it can ensure the stability in the east Mediterranean. In 2020, for instance, Greece signed a deal with Cyprus to build the deepest and longest undersea pipeline that would carry gas from new offshore deposits in the southeastern Mediterranean (Israel and Egypt) to the continental Europe. The EU and NATO can no longer afford to have a messy east Mediterranean. The stability in the East Mediterranean is a grave geopolitical issue. Greece is claiming back its rights. (I am not saying that – international law does. More on that below). Turkey, on the other hand, is suffering from one of the worst economic landslides in its history with reports that, in 2021 alone, the Turkish lira lost its value by 44%. The Turkish people are experiencing unprecedented inflation rates and foreign investment has stopped. At some point, the situation with the Turkish lira was so bad that companies, like Apple, stopped selling their products. (Apple has since restored its sales unit in Turkey). As people were getting angrier, Erdogan did what any sultan does – he looked for an enemy with the hope that it could unite the country against the enemy instead of him. In Turkey’s case, you just had to look down the road and there was your enemy. Part of President Erdogan’s strategy has been to contest the sovereignty of Greece in certain islands in the Aegean Sea. His message sounds unsurprisingly revisionist: unless Greece demilitarizes certain islands, then this creates a question of sovereignty (this goes all the way back to Turkey’s wrong interpretation of the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne and the 1947 Treaty of Paris). The response from the Greek government was strong. Again, none of this is new. But, it is still exhausting and annoying. You must be wondering where I am going with all this. I am trying to establish context of why the recent registration of the trademark “TurkAegean” has hit a nerve in Greece and, me personally A quick background on the trademark. Turkey’s 2022 tourism campaign focuses on its west coast, boasting places like Izmir, Ephesus and Ayvalik, all with rich history and deep historical references for Greece. According to the campaign, the “Aegean Region of Türkiye offers you beautiful landscapes, dazzling coastlines, immaculate beaches, pine woods and olive groves; perfect for nature lovers, photographers, history buffs and adrenaline junkies. Many popular holiday villages and fishing harbors are scattered up and down the coast”. While the United States rejected the application on the procedural grounds, 84 other countries, including the European Union, have allowed the registration of “TurkAegean” to proceed. By the time the registration became public, the Greek government was caught off guard; it committed to taking action, before having to apologize. . In Brussels, Greek representatives and pubic servants have also been vocal. Eva Kaili, Vice President of the European Parliament, questioned the legality of the trademark under EU and international law “as it is deliberately misleading, presenting the Aegean Sea, islands and coasts as Turkish”. Similarly, European Commission, Vice President, Margaritis Schinas, sent a letter to internal markets Commissioner Thierry Breton, requesting a review of the decision to approve Turkey’s application. The fact, however, is that under current trademark law and practice, it will be difficult to challenge the registration. One could advertise “TurkAegean” services relating to Izmir or Ephesus for instance and there is nothing prohibiting this. The only question that concerns trademark law here is whether the mark has become distinctive of that party's goods in commerce. Unlike Aegean, the term “TurkAegean” is not a geographical term, needless to say descriptive. In a similar vein, Greece could, for instance, apply to register “Cretalibyan” and, most probably, it would get it. But, it does not because it doesn’t want to and there is also this little thing called being a good neighbor. Here's the catch, however; the registration of “TurkAegean”, in fact, boxes Turkey out of insisting that the term is generic for a sea. Because of its trademark registration, Turkey can never claim that the term is a geographical indication for the Aegean Sea; there can never be a “TurkAegean” sea. The trademark prevents that. Essentially, any geopolitical claims Ankara may have hoped to achieve by doing this will not succeed. Moreover, this trademark may inadvertently become an asset for Greece as it makes its own claims for establishing the breadth of its territorial sea to 12 nm. Unlike Turkey, Greece is a signatory of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which establishes the rule. (The rule is also established through international customary law). Lately, Greece has been reclaiming its 12nm and, if Turkey intended to use the argument of “TurkAegean”, it would not stand. It is important for Greece more aggressive in the future. For one thing, it should become more proactive in protecting the names that are tied with its history and language, particularly when they end up misrepresenting Greece. As I am sipping my coffee, I type in my browser the name “aegeansea.com”. After a long wait I get an error message. I conduct a WHOIS search and I see that the name is registered (thankfully does not appear to be a Turkish authority), the Registrar is an entity in China (that makes me a bit nervous) and it expires in October 2023 (this makes me hopeful). I can only hope now the Greek government notices. Yes, it is personal! Good morning.

I would like to thank the European Internet Forum for putting this event together and for inviting me to share my thoughts on the need for digital rights and principles. During her opening remarks at 2021 Digital Assembly – “Leading the Digital Decade” – President Von der Layen said, among others: “We believe in a human-centered digital transformation”. Indeed, there is something profoundly human about the internet. The ability of independent networks to set their own rules while adhering to minimum standards that ensure interoperation is parallel to the democratic attributes of human autonomy, expression and participation. This basic architectural design, however, is often taken for granted. Current regulatory attempts from around the world, including in Europe, often seem to assume that the internet can’t break – that it just works – out of magic. The same way democratic societies have rules, so does the internet. And, this becomes particularly important as new ‘internet models’ emerge that seek to displace, replace or generally undermine the internet. It is for this reason that the timing of the “Declaration on Digital Rights and Principles for the Digital Decade” is important. It is a challenging time for the internet. This technology, which has transformative qualities, is currently being used as a weapon to threaten democracies and undermine users’ rights. For the past few years, Europe has been a global leader insisting on the need for regulation and clear rules that will allow the exercise of users’ rights while at the same time encourage innovation and economic growth. Striking this balance is not easy, given that a lot of the business models currently in place are designed around “surveillance capitalism” and they are the outcome of strong network effects and economies of scale. In this regard, the effort made by the European Commission and Europe’s willingness to commit to digital rights and principles is certainly commendable. The Declaration touches on almost all major points that are in need for immediate attention: it places people at the center of digital transformation; it highlights the need for connectivity and digital skills; and, it recognizes the need for users to be able to exercise their human rights within a secure internet environment. None of these aspirational goals can be fulfilled, however, without an open, decentralized and global internet. You see, there are various ways of networking – China’s way of networking is one of them. But, the internet way is rather unique. The internet is premised on a set of fundamental properties – engineers awkwardly call them invariants because they remain constant over time. The internet can evolve but these properties stay the same. This is what makes the internet so powerful. No matter how it changes, its properties remain unchanged. But, this internet is not a given nor can it withstand coordinated attacks. The internet is not a monolith nor should be treated as one. Its constant evolution, growth and innovation is a direct consequence of its original design. The internet’s properties are a mix of aspirational goals and pragmatic design choices and are significant because without them none of the goals listed in the Declaration can be materialized. Let’s run through these properties briefly:

These properties, aside from facilitating inter-networking, they also facilitate users’ freedom of choice, user participation and empowerment as well as a fair and secure environment. They ensured a resilient digital environment during the COVID pandemic. Unlike humanity, the internet was ready for this pandemic. The flipside of not having these properties is an internet that is based on topdown control where innovation is directed by a central authority, which is also responsible for determining what users can and cannot do. This is the China model and currently, at the international level, there is an ongoing debate as to which model will prevail. Because of this, Europe has a unique opportunity. As it sets the rules for the road, it must pay tribute to these foundational properties. Europe’s vision for the internet is one based on democratic ideals. An internet that departs from its original architectural principles cannot be a democratic one. So, my recommendation today would be to have these design principles enshrined in the declaration document and any other piece of primary or secondary legislation that emerges in the future. It is simply the only way to ensure that people are at the center of the internet. Thank you! A child and an adult are both inside a glass box. The adult is starting deliberately at the child as the glass fades to black.

Rather discomforting, right? This is the image the UK government wants to be engraved into the minds of every British citizen. According to an article published by the Rolling Stone magazine, the government plans to launch a campaign with the aim to “mobilize public opinion against Facebook’s decision to encrypt its Messenger app”. And, to make sure it captures the public’s opinion, the government is deploying tactics of sensationalism, exaggeration and emotion. This scaremongering is not a first for the UK government, which has been fighting against encryption for quite some time. Back in 2015, former Prime Minister David Cameron, pledged to ban online messaging applications that offer end-to-encryption. Although the ban never happened, since then, the UK has been on a steady course to ensure the government and law enforcement have access to encrypted communications. And, the Online Safety Bill, a legislation aiming to address content moderation practices and platform responsibility, appears to be encryption’s death sentence. One cannot help but wonder why the UK is so insistent to break encryption. Is it about power; is it about control? What is certain is that by intercepting encrypted communication, the UK government will have a front seat at the most intrinsic, intimate and personal conversations of its citizens. Imagine having knowledge of how your citizens say when they think they are alone, then imagine controlling it, and then imagine the possibilities of manipulation and abuse. I think you can get the picture of how expansive the powers of a government can suddenly become. This is surveillance at its most basic level and, in moving in this direction, the UK will soon be living Orwell’s 1984 nightmare. And, if this comparison is not compelling enough, then think that by doing this, the UK will be joining the company of countries like China in terms of user surveillance. The UK government’s argument is that encryption is an obstacle to ensuring the safety of children. Law enforcement agencies and charities have rallied behind this argument, suggesting that encryption hides millions of reports of child abuse and that end-to-end encrypted communication services are the main vessels for child grooming, child exploitation, sex trafficking and other child-related crimes. These claims create awe and one would hope that they are supported by strong, hard evidence; unfortunately, this is not the case. Although we all suspect that at some level encrypted communication services are used for illegal acts, but so is every technology. It is the nature of humans to use any technology for good and bad. And, the worrying part of the UK’s approach is that it appears disinterested or unwilling to take into consideration the good things that encryption brings. Privacy, security, trust – these are things that encryption achieves effortlessly. Encryption allows an LGBTQI kid to communicate without fear of bullying or, in many cases, persecution; it ensures that a domestic abuser is able to reach out for support and seek help; it helps activists and whistleblowers to come forward with information that holds governments and businesses accountable, which is the basis of every democracy; it helps all of us to exercise our freedoms and rights without the fear of someone snooping around. Of course, the safety of children is very important, but so is the safety of everyone else. And, without evidence to support that the ‘problem’ will be fixed by just banning encryption, is it really worth it? The UK government insists it is and for this purpose it has hired M&C Saatchi, involved in a controversial campaign during Brexit, to carry out its campaign. According to reports, the campaign will cost UK tax payers half a million pounds and, according to Jim Killock, Executive Director at the Open Rights Group, it is a “distraction tactic” seeking to manipulate the British public opinion. However, the truth about encryption is unequivocal: it is a necessary foundation for the internet and for societies. In many ways, encryption is the technical foundation for the trust on the Internet – it promotes freedom of expression, privacy, commerce, user trust, while helping to protect data from bad actors. Regulating encryption in order to hinder criminals communicating confidentially runs the significant risk of making it impossible for law-abiding citizens to protect their data. The main objective of security is to foster confidence in the internet and ensure its economic growth. In this regard, it becomes a valid question what such a ban will mean for the UK’s economic growth and innovation. In Australia, the Telecommunications and Other Legislation Assistance and Access Act (TOLA) 2018, which mandated tech companies to break encrypted traffic so law enforcement could get a peek at the online communication of Australians, is said to have resulted “in significant economic harm for the Australian economy and produce negative spillovers that will amplify that harm globally”.” There is really no reason why things will be different for the UK. It is important to note that, any technique used to mandate a communications’ provider to undermine encryption or provide false trust arrangements introduces a systemic weakness, which then becomes difficult to rectify. The fact of the matter is that once trust in the Internet is broken, it becomes very difficult to restore it. And, trust is what ultimately drives the use, consumption and creativity in the Internet. Ten years ago this week, the United States Congress proposed the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) which drew a great deal of criticism about its impact on the internet and human rights. Stakeholders from around the world, civil society, the technical community, businesses and academia, all joined forces against a piece of legislation that would undermine our trust to the internet and our ability to express ourselves without fear. What the UK proposes to do with encryption is no different; it will change the relationship users have with the internet for the worse. The UK may want to keep children safe, but by banning encryption, it will end up making everyone, including children, unsafe and vulnerable, while turning the UK into one of the most inhospitable internet and innovation hubs in the world. It is time for all of us to rejoice and fight for what is right: our right to a secure and private internet experience. This week, the Internet and its governance experienced a significant accountability failure. This failure had two faces: the first one concerned the Australian government’s choice to put pressure on tech companies to strike a deal with traditional publishers, led by NewsCorp. The second one was Facebook’s drastic move to block news’ content, essentially preventing the ability of its users to see and share news on its platform.

Let’s take things from the beginning. Earlier this year, the Australian government drew legislation “to level the playing field” on profits between technology platforms and traditional publishers. The Mandatory Code of Conduct would compel technology platforms with significant market power to enter in negotiations with registered publishers that earn over $150,000 AUS a year and are in compliance with the Australian news and media codes of ethics. On Wednesday, the law passed the lower house of the parliament and, with cross-party support, it is expected to pass the Senate next week. Google complied with the law. Facebook decided not to. This is not a first. Last year, the French government, in a similar move, instructed Google to negotiate in “good faith” with publishers, which resulted in Google negotiating a reported $76 million payout deal. The deal was the outcome of France’s attempt to enforce article 11, often referred to as the “link tax”, of Europe’s controversial copyright directive. There are a lot of issues with the “link tax”. Public Knowledge’s Harold Feld provides a very good account of what these are, here. Other sources also have pointed to the concerns over the uncertainty of its effectiveness. But, here, I want to talk a bit about the Internet. Not a lot of people talk about what all this is doing to the Internet. In 1997, Tim Berners-Lee wrote: “Normal hypertext links do not of themselves imply that the document linked to is part of, is endorsed by, or endorses, or has related ownership or distribution terms as the document linked from. However, embedding material by reference (sometimes called an embedding form of hypertext link) causes the embedded material to become a part of the embedding document.” So, the hypertext link is nothing more than a reference. Further down, Berners-Lee continues: “Meaning in contentSo the existence of the link itself does not carry meaning. Of course the contents of the linking document can carry meaning, and often does. So, if one writes "See Fred's web pages (link) which are way cool" that is clearly some kind of endorsement. If one writes "We go into this in more detail on our sales brochure (link)" there is an implication of common authorship. If one writes "Fred's message (link) was written out of malice and is a downright lie" one is denigrating (possibly libellously) the linked document. So the content of hypertext documents carry meaning often about the linked document, and one should be responsible about this. In fact, clarifying the relative status of the linked document is often helpful to the reader.” The reason everything is wrong with the “link tax” is stated above. It treats the hyperlink as something that carries a specific meaning. When hyperlinks are shared through platforms and search engines, they neither “endorse” nor “claim authorship”. The “existence of the link itself does not carry meaning”. This changes fundamentally the meaning and scope of hyperlinks. It ascribes to them a meaning they are not meant to have. This debate not just about Facebook or the Australian government or publishers. This is about the web. And, the implications of the “link tax” go further down the architecture stack. Here’s what Internet Society’s (and my boss) Andrew Sullivan said about the “link tax” in 2018: “The link tax, as described, well, to the extent it's ever been described, is actually impossible. It's technically impossible because nobody will ever deploy it. The only way that it will ever get deployed is if everybody agreed that I really want to be taxed.” That does not seem plausible. “And since it's unlikely that people are going to sign up to be taxed, then they're never going to click on a link that causes them to be taxed. All of the clients will simply not implement the necessary technical requirements to, you know, to cause the tax to take effect. And there are only two possibilities at that point. Either the government authority can say, well, you're not allowed to use a board compatible mechanism in which case the ‑‑ backward compatible mechanism in which case the internet is over. Or, you are allowed to use a backward compatible linking mechanism in which case only the backward compatible mechanism is going to be deployed by clients. Those are the only two possibilities and I've yet to have anybody explain to me how we get out of that. On the internet if you actually want people to deploy things you have to give them a reason to deploy it. “ So, this whole debate is not only about Facebook or governmental policy. It is about the Internet’s goal to be trustworthy, open, secure and global. Conditions like integrity, reliability, availability, accessibility matter for the Internet. They should matter in any policy. And, in the case of Australia, they evidently don’t. The Australia and France cases are not going to kill the Internet. They are deep cuts to its architecture, but they are not fatal. If the Internet dies, it will die of a thousand cuts. The BBC has reported that Scott Morrison, Australia’s Prime Minister, has already spoken with India’s Narendra Modi and is seeking international support. Here’s your thousand cuts – the possibility of the ‘link tax’ exploding as an international policy. So, to sum up: Australia’s Code is a terrible policy. Facebook’s decision was out of self-interest. The Internet is the casualty. Netflix was created in 1997 by Reed Hastings, who is still its current CEO, and Marc Randolph. In its early days, Netflix’s business model was based on DVD rentals, seeking to disrupt Blockbuster Video, which was the dominant actor in the United States. At the time, DVDs were only starting to make their appearance in the US market and offered a much better customer experience than videocassettes. Blockbuster Video was making a lot of money by renting them for a fee for a specific time. The fee would vary, depending on things like the s release date of a movie, late returns, etc. Hastings saw an opportunity to offer a flat monthly rate for all content and, he entered the market.

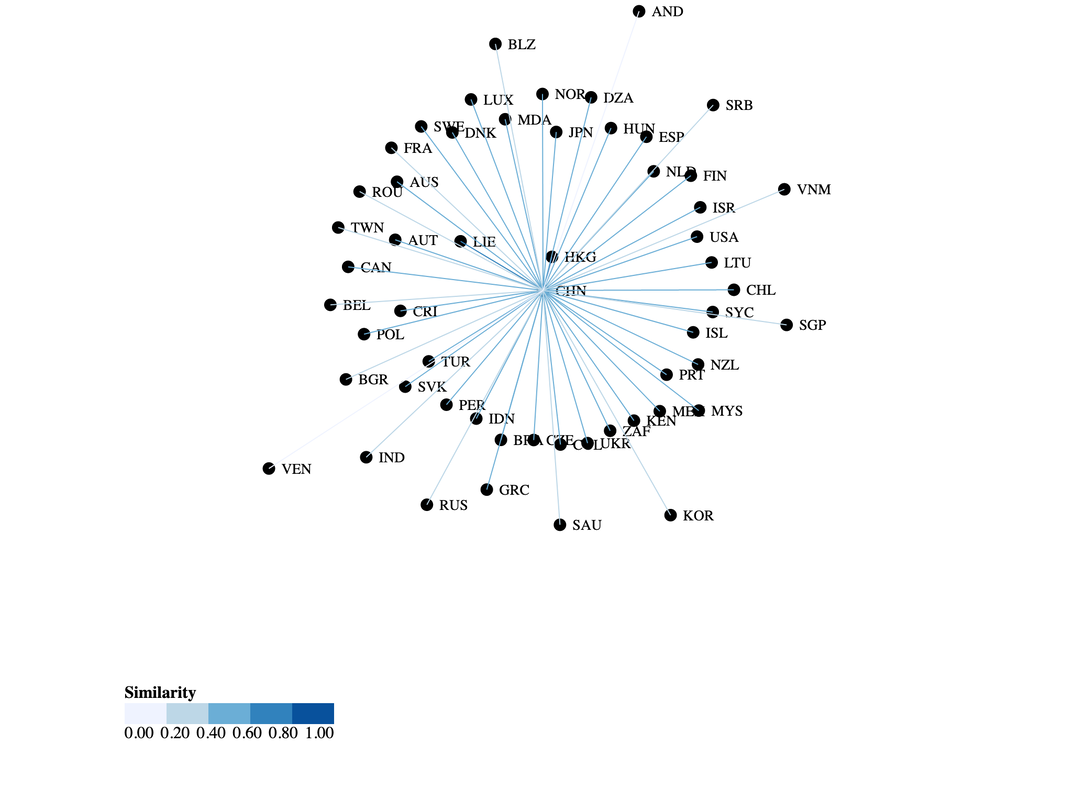

Netflix’s growth was quite substantial. From 300,000 users in 2000, the company grew double in 2002 and by 2005 it was counting 4.2 million users. In 2002, Netflix made its IPO debut in New York and, although the company had managed to outpace the business practices of Blockbuster, it was not until 2005 that it would adopt the feature that would place it as one of the primary contenders in the entertainment industry: streaming. By 2010, a user would be able to access Netflix via any portable or not device to consume content; the same year, Netflix expanded its operations to Canada. Over the next few years, Netflix would expand and, in 2016, it would end up rolling out its services globally (with the exception of China, N. Korea and Crimea). After adding original content in its services in 2012, Netflix has become a considerable contender in the entertainment industry having been nominated for 112 Emmy awards in 2018. It is currently counting more than 150 million subscribers internationally. Netflix soon realized that it had to find a new angle if it were to survive. Blockbuster Videos were no longer a threat – they declared bankruptcy in 2013 – but a new competitor was emerging as Netflix was adopting a new business model. Although streaming appeared to be a niche market for the company, its dependency on licensing deals by the large Hollywood studios meant that Netflix would need to find a new way to become competitive. That happened with the adoption of a strategy on original content and the company’s conscious decision to invest billions of dollars in original programming, taking advantage of its global reach. This bold move highlights the following disruptive strategy theories. Netflix started as a low-end market disruptor. Taking advantage of some of the policies customers used to find annoying in Blockbuster (mainly the late return fees) Netflix did not seek to offer something better, but something that was performing “good enough”. Netflix also realized that all other DVD rentals were following the same business model as Blockbuster, which meant that consumers were overloaded with similar products and similar business patterns. To this end, it sought to utilize the idea that it could provide the same product but improved. The improvement was ordering DVDs from the comfort of your home by paying a flat fee. No extra charges would be incurred. Netflix’s streaming, however, can also be seen as new-market disruption. What streaming did for Netflix is that it offered existing customers access to content cheaper –in the beginning, the service would offer lower performance for existing consumers (in those early days, Internet bandwidth would severely affect the streaming experience), but higher performance for non-consumers. As Netflix was rolling out its streaming service, Blockbuster considered that there was no incentive to go after the same service, effectively confirming the theory that a business cannot disrupt itself. To this end, Netflix created a whole new market that we only see now emerging and developing, with new entrants like HBO Max, Apple TV+ and Disney+ being amongst the competitors. Almost every time, disruption is an opportunity before it becomes a threat. This opportunity can be seized once the company realizes what the “job to be done” is. In the case of Netflix, it was the case of understanding how to help customers consume content any time, at any device. Streaming filled that void by offering customers a catalogue of content that were able to absorb. In a similar vein, Netflix saw an opportunity to address a problem that was at the core of the way audiences used to consume content: removing advertisements in the middle of broadcasting and offering content all in one go. As Netflix grew, the challenge was to ensure they remained faithful to their original business model and not try to emulate traditional broadcasting companies. Once they were dominant in the market, the temptation of adopting the traditional business model of offering content on a weekly basis was present, especially considering the costs associated with creating original content. Netflix, however, retained discipline and continued to integrate their organization to provide the consumption of content with an eye focused on the job to be done. Netflix never stopped offering content from other studios. Since that content is subject to licensing deals, geolocation services would have to apply; what this meant was that, despite being a global service, Netflix could not offer the same content to all of its users around the world. Organizing for innovation, essentially defining how Netflix’s resources could work together to achieve its goals, became very crucial. Netflix had a big choice to make: either stick with the content from the Hollywood studios, a choice that would ensure the company always depended on them, or identify and prioritize the criteria that would allow it to differentiate itself. This was achieved by investing in original content, which Netflix was able to control fully and was able to distribute at the same time to all its customers around the word. Netflix’s big challenge was how to create content that was easily consumable and was able to compete with traditional broadcasting incumbents, including ABC, HBO, Fox, Disney, etc. What is unique about the business model of Netflix is that it commoditized time – what a viewer was able to see on a Saturday at 9am was no different from what they were able to see on Tuesday at 10pm or Thursday at 3pm. Unlike traditional broadcasters, there is no ‘prime time’ on Netflix, and this allows Netflix the freedom to get rid of the advertising model, which has proven to limit the customer experience by breaking it in multiple segments. By adopting this business model, Netflix was able to demonstrate that it had moved from its original core competence: it was no longer about providing DVDs to its customers, but rather about connecting content creators and content consumers in order to ensure a more efficient relationship in the way content would be conceived, created and, finally, absorbed. Up until Netflix emerged as a disruptor, content was consumed based on a variety of factors: users, advertisers, studios, broadcasters. In disruptive strategy language, these factors of creating and consuming content created a series of interdependencies that provided for an ecosystem that was inflexible and quite bureaucratic. A lot of shows would be created and, if they could not generate enough advertising revenue, they would be cancelled, often at the dissatisfaction and frustration of consumers. In essence, there were additional extenuating circumstances, beyond consumer demand, that were able to determine the future of a given production. Netflix saw a great opportunity. Based on the data that it had generated from viewers’ habits, Netflix could integrate forward and offer personalized content to account for the interdependency. This is essentially what they did by partnering with various studios to produce original content. This collaboration included the interdependency of using Hollywood studios and content creators and the personalized information regarding customer content preferences, while letting go completely of advertisers. It is, however, logical to assume that over time this interface will become modular. At some point, Netflix needs to start looking for opportunities to have its own studios for the production of content. Based on all this, there are a number of things we could extrapolate. Netflix can either be positioned as a low-end disruption or new market disruption. In either case, there is an asymmetric motivation being created because incumbents are motivated to move up a market. For traditional studios, this would mean focus on the content they have exclusive rights to. It also means that current incumbents, given their relationship with telecommunications providers, might start considering how best to offer their service as part of package deals with mobile phones. This is an advantage Netflix does not have. According to the theory of disruption, Netflix will need to start moving up in the market offering more convenient and niche services in order to withstand the competition. You can easily imagine Netflix creating its own studios in order to cut the costs or start making more deals with actors and creators that tend to be popular with viewers, which it currently does. The same theory also suggests that incumbents, like HBO or Disney, will abandon low-end services and will start depending more on their niche products – HBO on shows like Friends and Disney on its massive catalogue of Marvell and Star Wars characters for instance – which can offer a higher margin to their businesses. In order to achieve all this, strategy will be key. When it started, Netflix was operating under a deliberate strategy, a conscious and organized action aimed at disrupting the business model of Blockbuster Videos. Over time, Netflix moved into a more emergent strategy, one that saw some unplanned actions, i.e. the basis for original content, to emerge out of the initiatives of parts of the organization. Now, it appears to be the case that Netflix is operating under a more deliberate strategy again. In order to survive what appears to be an increasing competitive market, Netflix will be required to again re-invent itself by moving into a more emergent strategy process.  The internet, as it exists today, is an artifact of a time in which global cooperation seemed reasonable, even inevitable. While the process of building the internet required difficult trade-offs—trading security for simplicity, for example—as a world we produced a system that, more or less, works together. But the free flow of information online is now under threat by growing fragmentation across national borders. This internet fragmentation is both as a driver and a reflection of growing fragmentation in the world order. The effort by the U.S. government to ban the Chinese viral video app TikTok is a reflection of this reality: a response by the U.S. government to growing Chinese influence manifested online, resulting in a splintering global internet. Internet policy and international affairs move together. Throughout the internet’s history, its major stakeholders have made trade-offs around how different social and technical systems interoperate. Security is one such trade-off. Contrary to popular belief, security was indeed considered in the internet’s original design; however, deploying a decentralized, open architecture was difficult to balance against security requirements. Erring on the side of creating interoperable building blocks, a trade-off emerged: make simple, fundamental elements and address security issues as they emerged. The system’s interconnectedness served as a shared incentive, and the internet as we knew it grew—though not without bumps along the road—to become global. But the global internet is now under existential threat from fragmentation. And the problem with fragmentation is that it puts global cooperation at risk, as differences in the internet across borders are predictive of international trade and military relations, according to research conducted as part of the University of California, Berkeley Daylight Security Research Lab. Such findings should recast discussions about internet fragmentation. Internet fragmentation does not concern narrowly the “free” movement of information (an ideal that has never been fully accomplished), nor does it merely challenge the internet’s “distributed” design, another ideal whose implementation has only ever been partial. Rather, a fragmenting internet is representative of and has the possibility of contributing to a fragmenting world order. Such analysis of a fragmented internet looks at different layers of the internet “stack”—the building blocks that cobbled together comprise the internet—to quantify, for example, how similar France’s internet is to that of Germany, Canada, or Thailand. Using these country-to-country comparisons, we produce a network graph, with each country related to every other in a web of national internets that are, more or less, interoperable with one another. The graph reveals clusters that correlate with everything from military alliances to trade agreements—even to political principles such as freedom of speech. For example, content blocking patterns in European Union countries are significantly more similar to one another than they are to non-EU countries. The same is true of NATO countries. Notably, these findings do not indicate that blocking policies cause, for example, freedom of speech to decline. Nor that restrictions on free speech cause a country to block websites. Rather, they indicate that website blocking patterns—the types of websites a country blocks—reveal information about a country’s position on the global stage. China’s blocking patterns are relatively unique, though they share similarities with Hong Kong and Lichtenstein.In one sense, the strength of that relationship is unsurprising. The internet is, and has always been, both a product and a driver of political realities on the ground. From the role it played during the Arab Spring in 2012 to the way it has been used as a tool to interfere with the U.S. elections in 2016, the internet is a powerful tool for driving political change. Internet fragmentation has always existed, but the fact that the internet has evolved the way it has, becoming global, is evidence that interoperability is more than just aspirational. World-scale collaboration, while difficult, is possible. It is as possible now as it was in the late 20th century. Interoperability opens doors to participation and invites collaboration. To this end, the internet, and the threats to its operation as a global system, are a continuous invitation to work together. Not to agree, per se, but to agree to continue talking. To continue speaking the same proverbial language. Interoperability is not an end in itself. It is a means toward achieving shared goals. As cross-border goals emerge, from containing COVID-19 to battling climate change, interoperable ways of observing and discussing the world become more crucial. Moving forward, policymakers must safeguard the fundamental interoperability of the global internet. Rules and legislation should prevent fragmentation, enshrining the principles of a decentralized network made from open, interoperable components. As our research shows, the rewards for doing so come in trade, military alliance and social freedoms. To get to these regulations, policymakers must understand the internet’s ecosystem. Climate change provides an illustrative example: Cooperation is necessary, but action is impossible without understanding. Our ongoing research serves a part—a small part—in making the interoperable internet more understandable, and immediately relevant, to policy. Dr. Nick Merrill directs the Daylight Lab at the UC Berkeley Center for Long-Term Cybersecurity. His lab produces tools for understanding and addressing critical security issues. Dr. Konstantinos Komaitis is the senior director for Policy Strategy and Development at the Internet Society. Note: this post was originally posted at: https://www.brookings.edu/techstream/the-consequences-of-a-fragmenting-less-global-internet/ The Internet could be reasonably claimed to be the global endurance champion of 2020. Not only did it manage to stand resilient and stay operational during one of the worst pandemics in modern history, but it also allowed societies to continue functioning. In fact, one could say the Internet was ready for COVID19; governments, for the most part, were not.

The Internet’s enduring value is a fact that has been repeatedly acknowledged by European legislators, even as they set out their rationale for the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act, new legislation that commissioners are comparing to “traffic rules” designed to regulate content and business online. Internet regulation has been at the top of every government’s policy agenda, from the United States to Europe to Africa and the Asia Pacific. The Internet has been integrated so much in the political machinery that regulation is now an inevitability. Only last week , the President of the United States, Donald Trump, tweeted that he would veto the National Defense Authorization Act, a significant piece of American legislation related to military funds, unless Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, the law that shields internet service providers from legal liability for content posted online, is repealed. In the meantime, France is working towards tougher rules for social media companies both domestically and at a European level in light of the terrorist attack on a schoolteacher in November. And, the UK’s Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, recently committed to fighting “disinformation” via “Online Harms” legislation, which is expected to be ready in early 2021. The concerns are, for the most part, legitimate: disinformation has pushed democracies close to a breaking point and, in some ways, it could determine the success or failure of the COVID19 vaccine. A renewed conversation around competition is long overdue as is the question on whether some of the existing legal rules are enough to address monopolies and market concentration online. Finding a balance between security and safety needs fast resolution. Regulation promises to fix all this. But as clear as it is that something must be done to address all these current challenges, it is equally clear that it must be done in a way that is fit for purpose for the Internet and the digital age. A recent global survey conducted by YouGov on behalf of the Internet Society has shown that over two thirds of people (67%) are not confident that politicians have a good enough understanding of how the Internet works to create laws to regulate it. That this legitimate concern exists does not mean that regulation should not happen. But it does indicate that regulation cannot go ahead on a basis of sensationalist arguments or unfit tools. Too often, Internet regulation is presented as a panacea for all ills, from abusive language to online fraud. But the Internet is an ecosystem and, just like any ecosystem, it is diverse, complex and dynamic. It is based on some fundamental design principles that have underpinned the Internet since its original inception. Regulation must uphold these principles and ensure that it does not create any unintended consequences for the way we communicate online. For its part, the Internet Society has created the Internet Impact Assessment Toolkit that we believe will help legislators create laws without causing damage to the ecosystem. The Digital Services Act may or may not contain elements that could harm the Internet; we will need to wait for its release to see. What we know is that the DSA promises to do for competition and intermediaries what the GDPR did for privacy: set rules that would then establish a global standard for platform regulation. It is expected to affect businesses around the world and require some drastic changes in their business models. This could also affect the Internet’s underlying architecture. How will the new rules be enforced? And what measures companies will be required to take will be key in determining the levels of participation and compliance. If there is one lesson to be learned from the GDPR, it is how lack of clarity and compliance costs can complicate and make implementation hard. The EU has admitted as much. Bearing this in mind is crucial as companies will start deploying tools to comply with the rules of the DSA. We should remain conscious as to how such tools may be created, who by and how effective they ultimately can be. Consider, for instance, the use of algorithmic tools for content moderation, which was a policy objective of last year’s copyright directive and has since then been implemented for other forms of illegal content. The DSA will require some form of content moderation on behalf of platforms. Algorithmic tools pose challenges, including , but not limited to, how they can negatively affect the Internet as an open, interoperable and general purpose network. Users could potentially be denied access to content that is needed for educational or research purposes. Automated filters have been responsible for taking down perfectly legitimate content that relates to war crimes or even legitimate speech. This could affect innovation and creativity, which is one of the main objectives the DSA aims to accomplish. The DSA has set the bar very high for itself. When it is released, it will become the first official attempt to articulate a legal environment for technology companies. But, the question of how well it manages to account for the Internet persists. It will be essential for the DSA to conduct an impact assessment analysis for the Internet as soon as the implementation phase kicks in. The Internet has held up and helped society get through a traumatic period. We owe it respect for its extraordinary service. |

|