|

Late on Friday, July 12th, Rev3 of the Global Digital Compact (GDC) dropped and went under silence procedure. In UN lingo this means that, unless one or more member states “break” silence, the GDC would be adopted as a consensus document. The deadline for anyone to “break” silence was Tuesday, July 16th at 3pm EST. Silence was broken just prior to the deadline.

The fact that silence was broken is not that surprising. The co-facilitators, Sweden and Zambia, chose to drop Rev 3 on Friday, late in the afternoon, effectively requiring capitals to read, absorb and coordinate with their New York ambassadors during the weekend. Monday was the only day, therefore, for all this to happen. And, that was simply not enough time. And, this brings me to the other point. The fact that member states ‘broke’ silence also comes to show how miscalculated was the move to call silence in the first place. All sides appear to have issues with Rev3 and what this means is that member states will now have to go back to the negotiations’ table. Quick reminder of what the GDC is The GDC is a process that was originally initiated by the UN Secretary General and, not member states. In fact, member states were preparing to discuss the issues the GDC focuses on next year, during the 20-year review of the World Summit on Information Society (WSIS). The GDC accelerated this conversation and, in doing so, it also changed much of the modus operandi on how this process would play out. The GDC is a less open and a contrived version of the multistakeholder process compared to WSIS. The GDC is part of a much larger conversation about the reform of the UN multilateral system and aims to contribute towards bringing states together in a collaborative fashion. Once agreed, it will be annexed to the Pact for the Future – a consensus-based document that is intended “to forge a new international consensus on how we deliver a better present and safeguard the future”. Rev 3 At first read, Rev3 appears to be solid. It hits all the sweet spots and uses the right words in most places (human rights, multistakeholder, etc.). It continues to be development focused, which makes it relevant and elevates its importance given the urgency in meeting the 2030 Development Targets. However, after a close read, Rev3 has a lot of issues and creates many gaps that can easily be exploited by any authoritarian government out there – the entire human rights section for instance is a gift to any country that seeks to evade its human rights obligations. Rev 3 also diminishes the role of the multistakeholder and collaborative governance and makes the GDC the main process that every UN institution and every process should be facilitating. This gives the GDC, and any organs that will be attached to it, power to determine where our digital future will be discussed and the processes that will shape it. The Good

Rev3 has explicit language on the need to develop “innovative and blended financing mechanisms” and to “invest in and deploy resilient infrastructure, including satellites and community networks…”. The recognition of blended financing is an important step towards recognizing where connectivity infrastructure investment has moved. Recognition of community networks is also a big deal as it recognizes the bottom-up and collaborative initiatives across the world that address connectivity gaps, especially persistent in small and/or marginalized communities.

Rev3 continues to retain the terms “open, global, interoperable” Internet. It is significant that these terms do not go away in any future revisions. The new term “reliable” is introduced in the text and this is one of the places where it can be misused for claiming a more state-driven notion of internet governance. It should be removed. The term “free” has also disappeared from the latest version which is unfortunate given that it seemed to have wider consensus. The Bad

Although the GDC attempts to address cross-border data flows, which has become increasingly complex over the past few years after many jurisdictions have been enforcing data localization laws, the entire data governance section is baffling. It is difficult to image how the entire section on “data exchanges and standards” will be implemented – how do you build a global data exchange system? Will governments be donating data into a global repository for access only by governments? And, how can the GDC guarantee that this access will not be abused and that is equitable?

Since the beginning, the GDC has put a lot of emphasis on AI governance. Member states have also signalled that AI is of critical importance. Both the US and China have recently led successfully separate resolutions in the UN that make this point as well as that AI is key to issues of development. Surprisingly, none of these resolutions is referenced in the GDC. Also, surprisingly, the High-Level Advisory Panel on AI discussions and report are not referenced. (The final report is not out but a leaked draft shows the inconsistencies between the GDC text and the recommendations in the report). Finally, when it comes to the governance of AI, the GDC opts for a predominantly multilateral structure. “We consider that international governance of AI requires an agile, multi-disciplinary and adaptable multistakeholder approach. We recognize that the UN has an important role to play in shaping, enabling and supporting such governance.” The word “adaptable” before multistakeholder is an attempt to dilute meaningful broader collaboration and to lock AI governance into the UN system.

Since the beginning of the GDC, one of the burning questions has been how this process will interplay with the WSIS+20 review next year. Paragraph 71 seems to address this stating that the WSIS+20 review should “identify how WSIS processes can support the implementation of the Compact”. It was always important that the GDC acknowledges the existing processes, like WSIS, and fora, like the IGF. However, the GDC gets this in reverse. The discussion should be about how the GDC serves and advances the WSIS Action Lines and the WSIS Tunis Agenda. Not the other way around. A better language could state: “We look forward to the WSIS+20 Review in 2025 to identify how WSIS processes can implement the Compact”. The ugly

In terms of multistakeholder governance, Rev3 has significantly watered-down the language on the value of multistakeholder participation. The term appears 13 times in the document and – in none of them – is there a recognition of the importance of the model for the internet and other technologies. Currently, paragraph 27 states: "We recognize that Internet governance must remain global in nature, with the full involvement of governments, the private sector, civil society, international organizations, technical and academic communities, and all other relevant stakeholders in accordance with their respective roles and responsibilities. We reaffirm the role of the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) as the primary multistakeholder platform for discussion of Internet governance issues." The text could be strengthened by adding that "Internet governance must remain global_and multistakeholder_in nature." In other places as well, like AI, the term must also be strengthened.

One of the GDC’s main selling points was its focus on human rights. The promise was that the GDC would advance human rights and would make international human rights law a core part of the document. Rev3 backtracks significantly on this promise and weakens the role human rights will end up playing in the GDC. The biggest issue has to do with the phrasing. Throughout the text, the obligations member states have, are “under international law, including international human rights law”. The word “including” is troubling and should be replaced by “and”. Adherence to international law does not equate adherence to international human rights law. What is even more frustrating is that the GDC text on human rights is not consistent with the text that is currently being negotiated in the Pact of the Future. Paragraph 11 of the Pact of the Future states: “Every commitment in this Pact is fully consistent and aligned with international law. We reaffirm the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the fundamental freedoms and protections enshrined therein and we will place human rights at the heart of our actions to implement the Pact. We will protect and promote all human rights, recognizing the universality, indivisibility, interdependence and interrelatedness and we will be unequivocal in what we stand for and uphold: freedom from fear and freedom from want for all without discrimination”. This text is more solid on human rights and the GDC should ensure consistency.

The GDC never fully understood the significance and role of the IGF and, in all versions, the language consistently reflected that. Whereas though the previous versions used language that was more supportive, Rev3 diminishes the IGF’s role to that of a “platform” for internet governance discussions. The IGF is a process, not a platform. It is process that is recognized in the Tunis Agenda and has been recognized by the UN’s General Assembly. It is not some platform that just discusses internet governance issues. Article 72 of the Tunis Agenda, clearly articulates the IGF’s mandate and it should guide the way the GDC talks about the IGF. Where’s the money coming from? Since the beginning of the process, one of the looming questions has been the financing of the GDC implementation. The GDC creates a number of new bodies, it calls for implementation by a swath of different stakeholders and proposes a number of new processes. This sounds expensive and lots of money will be needed. Where is this money going to come from? Who’s going to fund all these new activities? The GDC talks about private funding or philanthropy but let’s be real: the issues the GDC covers are so niche that won’t be able to attract the required financial resources. Member states will have to step in and provide some funding. Which member states will race to the start will be key. China is a likely candidate to provide funding especially given its increased interest in the UN development agenda. According to a report on China’s engagement in the UN development pillar by the German Institute of Development and Sustainability: “China’s contributions to the UN development system have grown significantly over the last decade. Its total contributions of roughly 451 million US dollars in 2020, are more than four times the size of its contributions in 2010”. Saudi Arabia can be another candidate, considering its increased interest in UN-related processes in the past few years. It is imperative that the GDC includes language that calls for transparency regarding the ‘who’ will be supporting the implementation of the GDC and its new bodies. Conclusion So far, the GDC gamble does not seem to be paying off. Digital issues are proving to be a sticking point for member state collaboration and that’s not surprising considering that for many countries they constitute part of their broader foreign policy agendas. Looking at the issues member states have broken silence over in Rev3, they may seem trivial to the untrained eye but on aggregate the GDC fails to capture the essence of collaborative governance and the role human rights should play in shaping our digital future. The Pact for the Future can still go forward without the GDC but it is unlikely at this stage that this will happen. It becomes imperative, therefore, that the GDC does not become a vehicle for changing the governance norms or that it ends up introducing new processes that can undermine the internet and the work of the communities that have supported it. Note: Unlike the Zero Draft, Rev1 and Rev2, Rev3 of the GDC is not publicly available yet. These comments are based on a leaked version of the text. The official GDC website is here: https://www.un.org/techenvoy/global-digital-compact There is an informal Ministerial Council meeting happening April 11, where telecoms ministers from the EU’s block will discuss, among others, the White Paper “How to master Europe’s digital infrastructure needs?”, which was published back in February.

Commissioner for Internal Market, Thierry Breton, had promised the release of a White Paper after his legislative campaign on network fees died last year. Just like he did with his proposal on network fees, he chose the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona to announce the White Paper’s release. This was not a coincidence; just like the network fees proposal, the audience of the White Paper is mainly the big five European telcos. Much like other countries around the world, Europe has set some targets for the Digital Decade. And, much like other countries around the world, these targets are ambitious. This is not necessarily a bad thing as long as Europe understands that, for achieving these goals, it will need to provide the necessary legal and economic incentives. Fostering sustainable economic, environmental and social benefits across Europe through digital transformation can only be achieved through collaboration and an ecosystem that is open, non-discriminatory and proportionate. The White Paper is nothing of sorts. There are a lot of issues in there that require the attention of everyone – spectrum allocation, critical submarine cables, development of 5G networks but there is hardly any attempt to lay down the complexity of these issues and outline the need for collaboration. It is a paper that points to the right things, yet it does so through the wrong lens. Telcos are part of the ecosystem; they are not the ecosystem. The White Paper aims at rethinking and broadening the scope of the current European electronic communications regulatory framework. One of the stated objectives is to address what is perceived as an uneven regulatory ‘level playing field’ between traditional telecom providers and cloud and other providers. The idea is to cover every provider of EU core networks and all networks on which public data transits, including a broad range of sectors and providers. The White Paper has a lot of problems in outlining a forward-looking strategy and, once again, the Commission is asking member states to buy into a half-cooked idea. The problem with this idea of course is that it will always be unconvincing because it seeks to advance telcos at the expense of an entire ecosystem – with its good actors and not so good ones. But, does this provide enough justification for the Commission to push an unpopular idea? For instance, the White Paper obviously cannot answer the impact such a drastic reordering of interconnection will have on certain networks. There are types of core networks which are private and they are currently regulated under the European Electronic Communications Code (EECC) as ‘electronic communications networks’. Beyond those, depending on the interpretation of the high level wording in the White Paper, this extended scope of regulation could apply to a whole host of entities including cloud providers, content delivery networks, organisations active in the IP interconnection market and their customers, Internet Exchanges, etc. Is this really the intention? The White Paper takes aim at interconnection even though there is no evidence that the interconnection market in Europe suffers. In fact, the White Paper notes: “There are very few known cases of intervention (by a regulatory authority or by a court) into the contractual relationships between market actors, that generally functions well and so do the markets for transit and peering.” However, the Commission is making the assumption that things may change in the future. “[…], it cannot be excluded that the number of cases in the future will increase.” Making assumptions on a range of markets that have evolved very rapidly in recent years, and continue to evolve fast, is one thing. Moving from these temporary, preliminary assumptions to suggesting major regulatory changes deserves much more serious consideration, scrutiny and stakeholder debate. In order, therefore, to prevent this scenario, the White Paper suggests a whole set of changes for a host of different actors in the Internet’s infrastructure chain. For the Commission, change means regulation which would entail a number of new burdens like some form of legal interception of users’ communications, new reporting and security requirements and the likely payment of universal service fees (a form of ‘network fees’). Yes, you heard it right – all this fuss is about making sure that telcos end up getting their half-cooked and rejected “fair share” proposal. Last year, an entire European ecosystem comprised of governments, small and big businesses, civil society groups, individuals, researchers, startups – all rejected the idea of direct payments from content providers to telcos. The reactionof BEREC, the independent body of European regulators, was also clear about changing the interconnection landscape in favor of telcos: “[t]he “sending party network pays” (SPNP) model would provide ISPs the ability to exploit the termination monopoly and it is conceivable that such a significant change could be of significant harm to the internet ecosystem.” The problem with bad ideas, like the one on network fees, is that they persist almost as readily as good ideas. Bad ideas have a long life and they have the tendency to outlive their originators. This is also true in this case as Europe’s bad idea has now taken a life of its own around the world, in countries like India, Brazil and elsewhere. There is no doubt that the tension between over the role telcos should have in the infrastructure of the Internet will be one of the defining Internet policy issues for the next couple of years. The long-awaited Global Digital Compact (GDC) zero draft dropped on Monday and there is a lot in it. It requires time to absorb it all but discussions are slated to start tomorrow so time is an issue. Also, bear in mind that this is the zero draft and, by the time this process ends at the end of May, the text will look very different. This means that there is no need to panic; at least, yet.

The zero draft gives a good snapshot of where the mind of the UN (and its member states) is. Here’s my high-level take. A quick reminder… Two years ago, the United Nations’ Secretary General initiated the GDC with the aim to tackle key digital issues through the lens of multilateral reform. Some key areas of concern were identified ranging from digital connectivity, to Internet fragmentation, the protection and governance of data, the application of human rights online, the regulation of Artificial Intelligence (AI), and, how best to promote a trustworthy Internet through the introduction of accountability criteria for misleading content. For two years, the co-facilitators of the process, Sweden and Zambia, held informal and formal consultations with both governments and interested stakeholders. Almost 200 written submissions were made from all parts of the world on views about the future of the Internet and digital technologies. Stakeholders participated in formal and informal consultations organized by the co-facilitators and the GDC was a topic of conversation in both New York and Geneva as well as at ICANN and the IGF. The GDC is part of a broader UN process, the Summit for the Future, which will lead to a governmentally negotiated but not binding Pact for the Future. The Summit is scheduled for September 2024. What does the zero draft do? The zero draft is a serious proposal. It is action-oriented, specific and fairly comprehensive. It focuses on the issues the community has been asked to discuss in the past two years and comes across as a real attempt map a path forward. What does it not do? Problematically, the zero draft fails to acknowledge the historical and institutional context of Internet governance and its link to development. Even though WSIS is mentioned, the role of the ITU and the work it has done for the past twenty years in following up and promoting the WSIS Action Lines is omitted. This leaves a big gap and creates a certain degree of duplication that is not necessary. Moreover, the draft introduces the term “multistakeholder cooperation”. This is instead of the historically used terms “multistakeholder governance” or “multistakeholder approach”. I am sure this is not intentional; however, the word “cooperation” is much weaker than “governance” or “approach”. In the latter case, stakeholders are given the opportunity to steer conversations and influence outcomes. Cooperation can be much looser. The most likely explanation for these mishaps is the fact that the New York branch of the UN is responsible for the GDC. Since the beginning of this process, the choice of New York over Geneva was questioned because it is usually in Geneva where such discussions take place. The ITU, the Human Rights Council, WIPO -- all major UN bodies are in Geneva. They have the expertise. Geneva is where the food is cooked. The good. There are some good things in the draft. The reference to cross-border data flows is a pleasant surprise as we all know how key it is for an open Internet. Expect this to be one of the things that will change – the G77+China group will most certainly object to the language, especially the one that points to the Data Free Flow with Trust framework, which is a G7 initiative. Recognition of the importance of open source is the other good thing. Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) has become a focal point in the GDC and it's a good sign that the zero draft acknowledges that for DPI to be effective it must be open, interoperable, based on open standards, human rights protections – much like the Internet. The draft commits, amongst others, to the promotion of the adoption “of open standards and interoperability to facilitate the use of digital public goods across different platforms and systems”. Finally, consistent with the consultations, human rights are also a core part in the zero draft. The language is not strong enough yet it seeks to commit states to apply international law. The draft suggests that human rights must become core part of the consideration on new technologies and can help with issues of inclusion and participation, but does not make any attempt to recognise some of the work that has already been done on this at the IETF and elsewhere. The bad. The section on connectivity is disappointing. The zero draft approaches connectivity in the same monolithic way it has been approached for the past twenty years. It puts all the eggs in the private sector basket and makes industry predominantly responsible for meeting the connectivity targets. The draft disregards the limitations and the poor results this approach has had. It also disregards the new connectivity models that have emerged. For instance, there is no mention or recognition regarding the community-driven initiatives, like Community Networks, that have been prominent in the past years. Nor is there any mention on blended financing models that have proven effective in addressing connectivity gaps. The other worrying thing is the recommendation for new structures, offices and processes. In total, the zero draft recommends the creation of five new ‘things’: a) a UN Digital Human Rights Advisory Service; b) a CSTD-led intergovernmental multistakeholder process; c) a UN-led international Scientific Panel on AI; d) a $100 million Fund on AI; and, e) a dedicated office for coordinating digital and emerging technology in the Secretariat. That’s a lot. But the question is resourcing and the money they will require to be set up. It will be interesting to see which countries will be stepping in to fund or support them. The ugly. The section on Internet governance is a massive let down. There is really no language per se that should make anyone cringe but the problem is not what the zero draft says on Internet governance; the problem is what it does not say. The words we have historically used to describe the Internet: “Open”, “Global” and “Interoperable” are completely left out of the document. Instead, the zero draft reads: “Promote a universal, free and secure Internet and take concrete steps to create a safe, secure and enabling online environment”. This language should raise some red flags to the west. When it comes to the use of the words “open”, “global” and “interoperable” , we use them to identify the single Internet – the one that is decentralized and not subject to top-down control. On the contrary, words like “universal”, “free” and “secure” have been inviting broad and discretionary interpretations. For instance, China has used these terms in all kinds of contexts. The other problem is the missed opportunity to boost the IGF. The zero draft recognizes the role of the IGF but it does not attempt to use its space, its community and its knowledge. For instance, the IGF could be used as part of the follow up and implementation. The GDC draft “encourages” everyone to “engage actively in its work with a view to advancing Compact commitments on Internet governance” but beyond that there is no real attempt to assign to the IGF a more specific role. Ultimately, the zero draft is all about centralizing discussions about digital issues within the UN system. The move to NY points to that as does the idea for creating a bunch of new things under the UN umbrella, the increased role of the CSTD the draft proposes, and the language about the role of governments. One would argue that, if the broader discussion is about multilateralism, this is to be expected. But, the zero draft negates the last twenty years and how they have informed, shaped and determined much of the Internet’s evolution. Key messages for New York:

The other day, a friend asked me about the status of the network fees debate in Europe. She has been following this issue in Brazil where national regulators have been emulating the European’s Commission thinking of having content and application providers pay a fee to telecommunication operators. She knew that it was an issue I was working on and was asking whether we had managed to ‘kill it’.

The answer is ‘no’, I told her. “But we did manage to shelve it, at least for the time being”. “How great! Congratulations. Europe must feel relieved”, she continued. That’s when I paused and realized that, indeed, Europe should feel relieved. We should be relieved because the open Internet gets to live another day; and, we should be relieved because, for the time being, reason prevailed. We need to take our small wins, whenever they come and, in whatever fashion, and celebrate them. I think It is time to celebrate this small win. Occasionally, in the Internet something pretty awesome happens: an issue would pop up that would make people come together and collaborate. In my twenty years of doing Internet policy, I can remember things like the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA) that made users take on the streets; the Snowden revelations that made the entire technical community come together and address surveillance; the 2012 World Conference on International Telecommunications, in which European telcos tried to kill network neutrality, unsuccessfully of course. The network fees discussions in Europe did just that. Without realizing it, the European Commission and the European telcos became the excuse for a highly diverse set of businesses and people from academia and civil society to come together and collaborate. Groups, like the content industry and big tech, that normally sit at opposing ends, have come together to fight the wickedness of network fees. This is remarkable and, in fact, it is the entire essence of the Internet. The Internet works better if people collaborate; for people to collaborate there needs to be a common goal; the common goal ensures that participants are focused and determined to cross boundaries and even practices; and, once they do, the outcome works for everyone and not for one individual actor. This is what Breton and the telcos failed to consider: the power of collaboration. The thinking must have been that only big tech, the direct recipient of this flawed policy, would speak up and they would easy to manage given the anti-big tech European sentiment. However, big tech was in fact the quieter voice: civil society organizations, academics, engineers, start-ups, public regulators, consumer groups and many others, we all became one voice against the European Commission and the big European telcos. This is a collective win. We should take every win, no matter how small. They don’t often come around. So, as the European Commission is preparing for its next move – in the form of a strategy paper regarding legislation for the admittedly brilliantly branded “the DNA Act” (or Digital Network Act) – we can take a moment and breathe a sigh of relief. The open and global Internet will get to live another day in Europe. On October 2nd, 20 CEOs of European telecoms operators published an open letter on the future of connectivity. Calling for a “Fair Share legislation” and warning that “Europe must act to protect its digital future”, the aim of the letter was to remind everyone that they are not going to back down: telcos want big tech to give them money and insist that the European Commission recognizes them this right even if it means breaking network neutrality, changing the way interconnection agreements are made and work and, effectively, putting the Internet model at risk.

The letter repeats some untruths; for example, this idea about the presumed investment gap or the fact that “fair share” and network neutrality rules are compatible; it also persists on mistakenly calling content and service platforms “large traffic generators”. I understand it is meant to sensationalise the debate, but it is fundamentally wrong; (I have lost the number of times this mistake have been addressed; users generate traffic and, it is users who pay telcos for access to the services of these platforms. This is a fact!) Effectively, the letter says nothing new and, I am, frankly, surprised it was picked up so fast by the Financial Times. It goes to show the power dynamics that are at play in this debate as other, more objective, letters have not had this type of coverage. The letter, however, serves an additional purpose – it gives support to the European Commission to continue pursuing this unwanted file. It has now been more than 20 weeks since the closing of the European Commission’s consultation on “fair share” and, nothing has been made public yet. With a rumored number of around 450 submissions and, the fact that the Commission outsourced their analysis, it is really unreasonable that the comments outcome summary are still not released. I think we can assume that the Commission does not like what Europe’s stakeholders have said. Yet, without the results we cannot be certain. (If you ask me, I bet that European users have not given the mandate to the Commission to proceed with this policy). One part I found interesting in the letter is the following: “The European Commission has been clear that any regulatory mechanism would be implemented in full compliance with Net Neutrality rules. We agree. In addition, it should be stressed that the underlying objective of the Open Internet regulation is to ensure unfettered access to the internet for end-users. This objective is undermined by the lack of investment capacity on the part of telecoms companies, jeopardizing the build-out of new capacities in the network, so that operators can meet the data growth. An obligation to negotiate with operators a fair and adequate contribution, with a dispute resolution kicking in if negotiations fail, would help alleviate this challenge.” I am not going to engage on the network neutrality argument again because we have a very clear picture of how network neutrality is interpreted in Europe and it comes from two decisions of the European Court of Justice (ECJ) – both technological and economic discrimination are against the Open Internet regulation. The end. The European Commission can make any statements to the contrary but between the Commission and the Court, I would go with the Court. The point that caught my attention, though, is the idea of imposing a requirement for negotiations between telcos and big tech. (This is not new; but, for some reason this time around, I read it as an indication of where things may be heading.) So, here are some thoughts about a negotiation process:

The conversation on “fair share” is far from over. The Commission is running out of time, given the election cycle next year, so we should expect that we will see something pretty soon. At this stage, it’s anyone’s guess which way they will be heading. But if there is a chance that the negotiation model is where the Commission may seek compromise, it changes nothing. It is what telcos wanted all along and they will be getting it through the back door. The other day, I came across a blog post by one of Europe’s biggest telecommunication operators, Spain’s Telefonica, arguing that the “fair share” debate is not about network neutrality and that its reference is some sort of a ploy by big tech to “distort and distract from the crucial issue: [the fact that] Europe needs investments in digital infrastructure for the benefit of all Europeans in the future”.

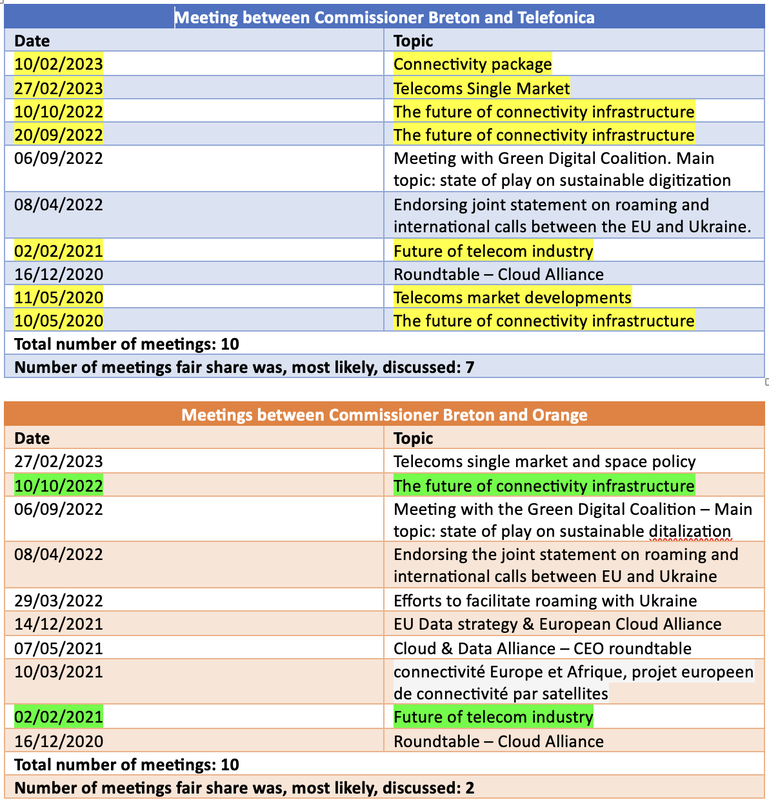

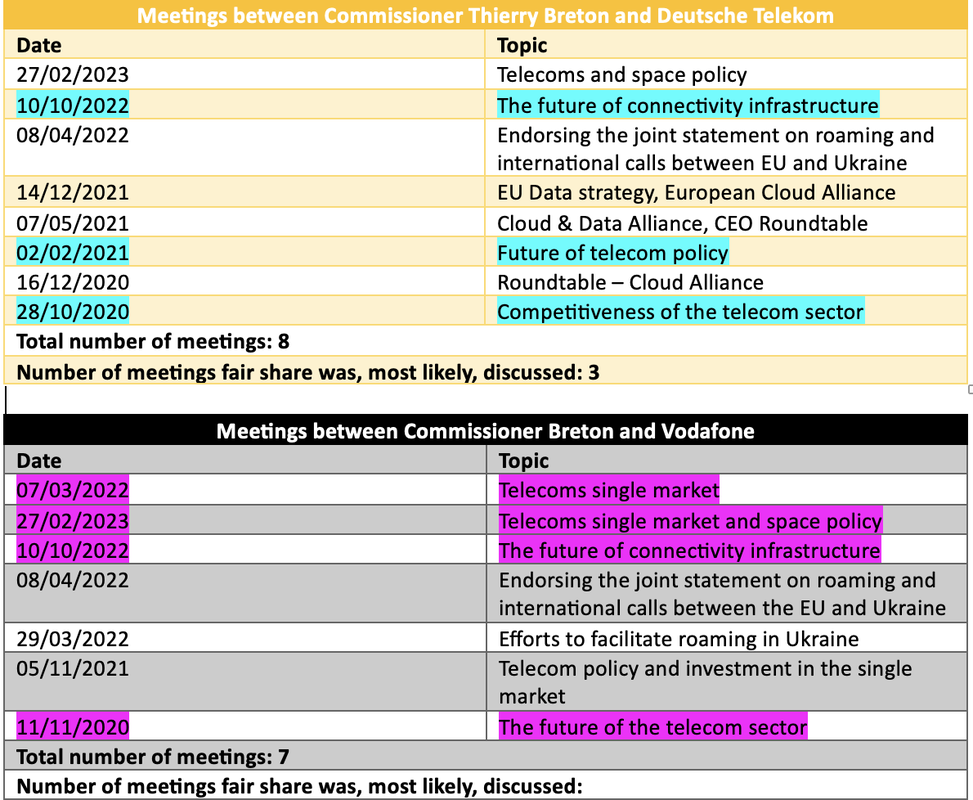

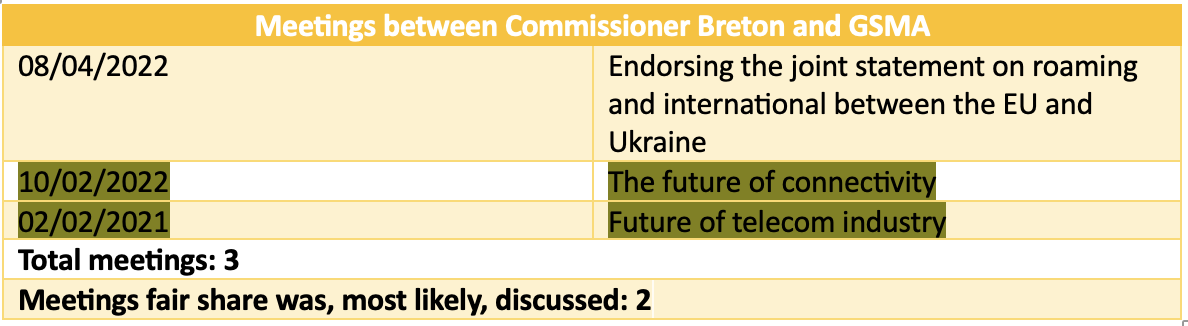

Let me start by pointing to the hypocrisy of this statement. Let’s not forget that it was the telcos that created an issue out of nothing by piggybacking on the wave of legislation targeting big tech; the hope is that other legitimate concerns policy makers have about big tech will clout their judgement so much so that they believe the unreasonable complaints of telcos. And, these claims are unreasonable; we know this by now. The majority has spoken: there is no market failure, there is no need for regulation, there is not a problem. Yet, here we are talking about a non-problem for more than a year now. So, let’s not forget who opened the network neutrality can of warms. Telcos did. But let’s go back to the reason for this post: the idea that the current debate is not about network neutrality. Let me start by saying that, unequivocally, the “fair share” debate is about network neutrality. There is no question about it. It always has been and it will always be. It was a network neutrality issue back in 2012, when European telcos came up with this plan and it continues to be today. As I asked back in 2022, “How is it possible to talk about changing the way interconnection works in the Internet and not talk about network neutrality? How is it possible to consider allowing certain commercial transactions to replace years of peering arrangements in the Internet and not talk about network neutrality? Pretty simple, you cannot”. And, if you don’t believe me then you must read what Barbara van Schewick, one of the world’s leading experts on net neutrality, a professor at Stanford Law School, and the director of Stanford Law School’s Center for Internet and Society, has written: “Net neutrality seeks to ensure that we, not the companies we pay to get online, get to decide what we do online. Users determine what apps and services are successful, not ISPs. Art. 3(3), subparagraph 1 of the Open Internet Regulation ensures ISPs cannot interfere with our choices by prohibiting ISPs from discriminating among applications, content, and services. In 2020 and 2021, the European Court of Justice held that this rule prohibits ISPs from treating applications differently either technically or economically. That means an ISP may not slow down Netflix or put its own video service in a fast lane; that would be technical discrimination. An ISPs may not charge a different price for the data used by WhatsApp than for the data used by the ISP’s own messaging app, either; that would be economic discrimination. The network fee proposal seeks to charge selected content providers but not others. This treats content providers that have to pay differently from those that are exempted. This kind of economic discrimination directly violates Art. 3(3), subparagraph 1.” Of course, the concerns over network neutrality are not promoted or voiced by Big Tech only. Civil society, consumer organizations, members of the European Parliament and governments have all expressed concerns about the implications a “fair share” proposal can have on the established principles of network neutrality and the ability of users to access the content they pay their ISPs for. Telefonica's blog post conveniently avoids to mention them. They pin it to big tech because, playing the “big tech does everything wrong” card, might actually distract from talking about the real impact of this policy on users, the European digital market and the Internet. There is really no way to getting around the fact that forcing some apps and services to pay ISPs is the definition of network neutrality violation. There is also really not getting around the fact that, if this initiative goes forward, Europe will be solely responsible for undermining one of the most fundamental and hard-fought principles in the Internet. Just because you want something not to be a problem, does not mean it isn’t. And, this is the case with network neutrality; just because telcos and the Commission are saying it is not an issue, it does not make it a non-issue; especially, when all evidence points to the contrary. For better or worse, we are now stuck with this debate. It would be a grave injustice to allow telcos to narrow it only to the bit that makes them comfortable. Network neutrality should be on the table! At the Telecom (TTE) Council meeting in Luxembourg on June 2nd, the fair share proposal suffered its biggest blow to date. According to Reuters, “telecoms ministers from 18 countries either rejected the proposed network fee levy on tech firms, or demanded a study into the need and impact of such a measure”. Numbers don’t lie. To have 18 of the 27 EU member states express serious reservations is indicative of the proposal's problems. And, if it was any other issue and any other Commissioner, this number would have prompted the proposal's immediate reconsideration. Not, for this Commissioner though. The issue persists in the mind of Commissioner of the Internal Market, Thierry Breton; this raises a lot of questions (and concerns). The fair share debate stopped being about facts around six months ago. As soon as it became public that the Commission’s Internal Market division is willing to reopen ETNO’s 2012 idea on network fees, an overwhelming majority of the EU’s stakeholder community chimed in with evidence about its dangers, facts about its unlikely success and concerns about its impact on the Internet and Europe. Over the course of this past year, the arguments about the way the idea of network fees will affect consumers, competition, investment and the Internet have been repeated to the point of exhaustion. Even BEREC, the body of national telecommunication regulators, has repeatedly said that there is no proof that any of this is necessary. Yet, Commissioner Breton insists on presenting a different reality. In this reality, only Deutsche Telekom, Orange, Vodafone, Telefonica and Telecom Italia – and their affiliates - are right. Commissioner Breton is also right. But everyone else is wrong. Naturally, this does not make any sense, but it does beg an interesting question: why this level of persistence? I have been asking myself this question for quite some time now. For sure, there is an element of Breton’s strong wish to boost European companies; but, the most important factor seems to be that Breton, a former telcos CEO, can’t seem to get out of the telcos' mindset. If you combine these two considerations, then the result takes the form of the toxic “fair share” proposal. Breton’s borderline obsession with this issue, despite being overpoweringly rejected, does not sit well with me and, should not sit well with any European citizen. I decided, therefore, to explore a bit the current relationship between EU telcos and Commissioner Breton. The European office of Transparency International offers a great Integrity Watch EU tool and a quick search on the meetings Breton has had in the past three years with stakeholders is quite telling about the levels of access telcos have had as opposed to civil society and other NGOs. The tables below show the number of times telcos have had meeting with the Internal market unit, to which Breton was present. In some of the meetings, all telcos were present, other meetings were bilateral. Based on the topics, it also looks that some meetings were more directly related to "fair share" than others. It is impossible from the tool to know whether other stakeholders asked for a meeting and got turned down or they did not request a meeting at all. But, in the end it does not matter: Telefonica, Orange, Vodafone and Deutsche Telekom have been meeting with Breton on quite a regular basis for the past three years, deliberating on how best to reform the telecoms sector, discussing issues of infrastructure development and without the participation of other affected parties. At the Mobile World Congress, earlier this year in Barcelona, Breton even posted a tweet about another private meeting where the "financing the infrastructure of connectivity tomorrow" was discussed. When I look at these tables and the number of meetings, it is obvious that we are talking about downstream lobbying or the “attempt to influence particular policy measures that might directly affect the industry concerned”. Of course, every company, telcos and big tech alike, engages in some form of downstream lobbying. (Unfortunately, that's how lawmaking works these days, but that's a whole different conversation.) But when downstream lobbying is combined with “cultural capture”, things are totally different. A study conducted in Quebec, Canada showed that “cultural capture” can happen “when public officers come from the same private sector now within their purview. Based on public officer’s allegiance to their former industry, lobbying is de facto exerted, “from within”.

This revolving door situation – the fact that Commissioner Breton comes from the telco sector and is now a Commissioner responsible for much of its future – can lead to regulatory capture or “the result or process by which regulation […] is consistently or repeatedly directed away from the public interest and toward the interest of the regulated industry, by the intent and action of the industry itself”. This regulatory capture becomes even more profound when associated with “cultural capture” or the idea that “those in charge of the relevant state entity [internalize], as if by osmosis, the objectives, interests and perception of reality of the vested interest they are meant to regulate”. This partly justifies the reality Breton is presenting to the world regarding the state of infrastructure investment in Europe. But it is a reality that no one seems to buy into apart from a handful of telco CEOs. And, the worst part of this reality is that the Internet’s topology is changed, consumer concerns are non-concerns and telcos are fully in charge of the way European users communicate and absorb information. It is a reality that significantly departs from the established norms of evidence-based and unbiased rule making. It is a reality that will set Europe back. In it is submission to the United Nations’ Global Digital Compact (GDC) process, the Secretary’s General’s initiative for the future of the Internet, the European Union, on behalf of its member states, writes: “The COVID-19 pandemic heightened the importance of access to secure and trustworthy digital infrastructures and technologies, underpinned by proper regulation including in the field of health. This includes the protection of users' rights online and the creation of fair, open and contestable online markets. Net neutrality is a key issue to be maintained and protected.” [emphasis added]. This level of hypocrisy is exhausting and dangerous. Hypocrisy hides the truth from people, it shields legal wrongs from public scrutiny and, ultimately, undermines the very rule of law. The Commission must kill the so-called “fair share” before it is too late. A couple of months ago, I wrote an article about the Global Digital Compact (GDC), the United Nation’s new governance initiative for the Internet, and its goal. In that article, I did wonder whether the intention of the GDC is “to create a centralized system, where the UN sits at the top.” After reading the Secretary General’s new policy brief, I am convinced that this is the case.

The first thing I feel is worthy of mentioning is that, in the past twenty years of Internet governance discussions, it is the first time, at least to the best of my recollection, that a UN Secretary General produces such a detailed policy document for the governance of the Internet. (Former UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan, had shown interest in the Internet, but that was after his tenure as the head of the global intergovernmental body). So, this policy document, irrespective of where or how it will end up, is quite a big deal considering its source. For its most part, the document hits the right tones and uses the right language – terms like multistakeholder, open Internet, human rights and collaboration appear throughout and make the case for a new process that will have these features at its core. And, if it were 2005 and Internet governance was still in a nascent stage, this policy brief would make a lot of sense. The reality is, however, that after all these years of experience in Internet governance, this document offers nothing new to the Internet governance discourse. In the Internet governance microcosmos, the entire idea of “digital cooperation” upon which the entire GDC process is premised, is as old as the hills and has already been tested. After 2005, the agenda of the World Summit on Information Society (WSIS) called for enhanced cooperation to help governments reach consensus on international public policy issues; after a series of failed attempts and a rough ride in the UN system, the whole idea of enhanced cooperation was put to bed. Now, it seems to be back and rebranded as “digital cooperation”. Just like the Secretary’s General’s “Common Agenda Report”, the policy brief identifies the same seven core issues that the UN should focus on, including connectivity, AI, human rights, Internet governance and data governance, amongst others. But the vision of the Secretary General comes full circle in the section of the document entitled, “Implementation, follow up and review”. There the proposal recommends the creation of “an annual Digital Cooperation Forum” tasked to support the implementation of the GDC. The Digital Cooperation Forum will effectively be a new process based on an old idea. And, what about the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) you may ask? It will continue to exist but, by the sound of it, it will have a supporting role. “Existing cooperation mechanisms, especially the Internet Governance Forum and WSIS […] would play an important role in supporting implementation, providing issue and sector knowledge, guidance and practical expertise to facilitate dialogue and action on agreed objectives”. You can almost sense it that, should the SG’s proposal become a reality, the IGF will be displaced, an outcome that would be the result of a proposal that lacked the consultation of the wider Internet community. It would shift the IGF to a role to implement a vision that has not been set bottom up; a vision that appears more bespoke to government needs rather than the Internet’s or the multistakeholder model; a vision that will be “initiated and led by Member States with the full participation of all stakeholders”. I’ve said in the past that the IGF is not perfect and it has its own problems and limitations. Still, it is a space that has gained the trust and legitimacy of a diverse set of stakeholders – governments, civil society, businesses, academia, international intergovernmental organizations, NGOs, the technical community – you name it; it is a process that already has the buy-in from the majority of the global Internet community. Why demote it then instead of trying to fix it? The answer seems to lie in centralization. If I am reading this right, the role of the Digital Cooperation Forum will be to centralize different multistakeholder processes under its umbrella, ranging from the Christchurch Call to ICANN and the IETF (frankly, I really am looking forward to the day the UN attempts to ‘demand’ things from an organization like the IETF.) “The Digital Cooperation Forum would accommodate existing forums and initiatives in a hub and spoke arrangement and help identify gaps where multistakeholder action is required. Existing forums and initiatives, many of which are listed in Annex 1, would support the translation of Compact objectives into practical action, within their respective areas of expertise. The Digital Cooperation Forum would help promote communication and alignment among them and focus collaboration around the priority areas set out in the Compact. Internet governance objectives and actions, for example, would continue to be supported by the Internet Governance Forum (IGF) and relevant multistakeholder bodies (ICANN and IETF).“ Centralization and top-down processes are tricky when it comes to the Internet as they tend to slow things down and create unnecessary bureaucracies and chokepoints. Being decentralized itself, the Internet tends to respond better to looser and more agile governance arrangements that make room for fast-paced action. The UN system is the antithesis of this. It is slow, cumbersome and bureaucratic. It does not have a good track record of developing processes that have the flexibility to respond to the Internet’s evolving pace. Yet, the proposal really does insist on this solution. “[W]e have yet to put in place a global framework where states and non-state actors participate fully in shaping our shared digital space […]. The UN [..] is the only global entity that can convene and facilitate the collaboration needed”, the document reads. That’s partly true though. Indeed, the UN is the only global entity that we have; but, convening and facilitating collaboration does not need to happen within the UN system necessarily. We have plenty of global multistakeholder initiatives that do not require UN oversight or intervention. The Christchurch Call is one such initiative supported by 58 governments and 14 online service providers, while civil society is participating in an advisory capacity; the network keeps growing. The Freedom Online Coalition (FOC) is another governmental initiative in which civil society and the private sector participate through an advisory network and working groups. Neither of these processes is, of course, panacea but the claim that we have not in place global frameworks is limiting in how we should understand Internet governance and global collaboration. The more one reads the document, the more it becomes clear that the Secretary General is invested in trying to identify ways to address some core Internet-related issues, including Internet fragmentation, AI and content moderation. There are legitimate reasons for wanting to do so – governments are already producing regulation in most of these areas, the global Internet is indeed under the strain of fragmentation and AI is currently generating more questions than answers. The question though is whether the UN is ultimately the right place for these conversations? The current state of the world does not seem to fit the Secretary General’s narrative about collaboration. In other words, the idea that governments will all gather and work in good faith for the better of the Internet is not realistic. How is it possible to believe that “human rights” can become “the foundation of an open, safe, secure digital future” when you have China and other countries with questionable human rights track record participating? How can the UN guarantee the application of human rights when in other processes it hosts human rights are, in fact, at risk? How can the UN assure multistakeholder participation will be upheld in a new process with new rules and new required resources? As the UN ventures to create this whole new process, with New York being the center of operations, participation will become a crucial issue. Civil society, in particular, has historically struggled to participate in Internet governance fora – for the IGF it often has to do with geography; in the case of the GDC, it will be both geography and possibly new rules of procedure. Will the GDC and its proposal for a new Digital Cooperation Forum allow for the same levels of participation as the IGF does? Will this new forum rotate around the world, like the IGF, or will it be held exclusively in New York’s headquarters? If the latter, what about issues of visa? Let’s not forget that it was only a few years ago that people from certain countries were banned from entering the US. Is it a smart move to have Internet governance discussions centralized in New York? After so many years of experience, these questions should not exist; yet, here we are asking the same questions we were asking back in 2005. In the end, the GDC feels top down, somewhat disconnected from what the Internet needs or how the Internet community operates. If I were reading the SG’s policy document without knowing anything about nothing that has transpired in the past twenty years, I would think that this is potentially the way forward. But a lot has happened in the past twenty years and, if there is one thing, we all have learned is that forced collaboration leads to tension and weakened structures. The GDC may be an opportunity to address some things we have missed in the past twenty years; or, it may not. If we really want to find out, however, the conversation must have a different starting point, which is reaffirming, upholding and strengthening existing multistakeholder processes and rules of procedure; we should not be creating new ones. The other day, I came across a quote from Wiktoria Wójcik, the cofounder of InStreamly, a Polish startup: “I don't know what will happen. I feel like I have no power over it. I have no real say in this discussion. And the biggest issue is that it's so surprising because nobody's even talking about it”. She was referring to the "fair share" conversation in Europe and it made me cringe.

I have been following this debate in Europe since it started a year ago and my views have also been clear. But, the despair I read in Wiktoria’s statement hit me. No European citizen should feel this helpless. The European institutions were created to listen to the people of Europe; their entire existence is based on that very responsibility. Yet, here we are. Wictoria is a member of a group of Polish startup companies; they are the last group to voice their concerns about the European Commission’s proposal on network fees. (The group is partly funded by Google and Microsoft according to their transparency register.) Who ever funds them, the fact is that Europe needs a robust startup ecosystem to become globally competitive and relevant; Europe should be fostering a predictable environment for startups, not one that causes despair. Regulation is necessary but regulation for the sake of regulation is unpredictable. The European Commission’s apathy to such concerns has been nothing short of frustrating. This whole thing is nothing more than the result of effective lobbying. (In this moment, you will rightly point out that everybody lobbies; big tech does it; big telcos do it; everyone is doing it.) But, let’s make something clear about this specific situation: if there is one issue where lobbying can really screw the global Internet, this is it! I fully appreciate that, when we hear such grandiose statements about the Internet, most of us think they are exaggerations. Frankly, most of them are; but, not this one. If you allow access networks even more power than they currently have, if you recognize the right of termination monopoly over the way content is delivered to users, if you unnecessarily intervene in the functioning arrangements on how networks interconnect, then you are effectively changing the topology of the Internet. You are essentially saying that there is a small number of networks that is more important than all the others networks. You are granting these networks the keys of the Internet; and, you tell them that from now on they get to decide on everything from innovation to user experience. This is not the Internet. This is the telecoms network reimagined. The question then is what will the Commission do? Next Friday the public comment period ends and the comments will be in. The Commission has decided to outsource their analysis and synthesis to an external consultancy firm, but it remains unknown which firm has been awarded the tender. Soon though, we will find out where European stakeholders stand on this idea of a “fair share”. Equally interesting will be the European Commission’s next move after the votes are in. If the consensus is that this whole policy is unnecessary, the Commission will have a hard time explaining its unedifying support to the EU big telcos. If the comments end up somehow being in favor of the proposal, the Commission will have the extremely hard task of managing the considerable resistance by European stakeholders. In both cases, because of the way the Commission treated this issue this past year, it has backed itself to a corner. The same seems to be happening with the EU big telcos, given how half-baked their proposal is. For the past year, telcos have provided no information about things like how they envision this financial relationship to be established, for how long, under what criteria, accountability provisions, checks and balances, etc. The proposal was limited to just: we are only interested in direct payments. If things don't turn out the way they hope, it will require a lot of trust building with a wide range of stakeholders. This will not be easy. The bottom line is that we are all losers no matter how things turn out. This whole process has created and fostered an antagonistic environment, while the Internet, and its infrastructure, are all about collaboration. Now that I think about it, despair might be more fitting to describe this whole process. The other day a friend of mine pointed me to a post written by the Director of EU Affairs for Telefonica. The post is entitled “You have not seen this movie before: fair share is not a remake”. The title is quite catchy, yet predictable and not surprising. Telefonica is one of the big telecommunication actors in Europe that are pushing hard for the fair share debate. Frankly, I was about to push this to the end of my “to-read” list pile, but the subtitle really caught my attention. “The fair share contribution of large content platforms to network sustainability could be the catalyst for the transformation of telecoms operators in Europe from telcos to techcos towards achieving Europe's most critical goals.” I find it very interesting that the transformation of the telecommunications industry towards a more technology-oriented, Internet-adapted sector is dependent on the funding that is produced by the technology companies. I also find it rather fascinating that after decades of trying to push telecommunication companies towards accepting that the Internet is here to stay, we are now in a place where telcos want to become “techcos”. (By the way “techcos” sounds to me like a snackable treat but, hey, I should not the one to pass judgement on inventing names – I am pretty terrible at it). So, I started reading it. And, here’s what I realized: it is true that the fair share debate is not a remake; but it is definitely a sequel. And, just like any sequel, it is tired and not very innovative. Before going into the details of the post, one point that I think deserves attention: for the past year, European telcos have been inside their own echo-chamber, reusing, rehashing and repeating the same arguments. In the post, any arguments presented are referenced back to arguments made by Telefonica. There is not an attempt to point to any outside sources that could justify any of the claims that are being made. Personally, this rubs me the wrong way, especially considering that the arguments about why the fair share is bad policy for Europe are coming from so many different sources. You can find them here and here and here and here and here and here and hereand here …. So, let’s see what the article says: “A range of stakeholders try indeed to portray fair share as a debate held and closed ten years ago in Dubai during the ITU WCIT Summit. Needless to bring it back because nothing in the fundamentals of how the Internet works has changed during the last decade and we need to preserve it this way to keep it as the generative engine for openness, innovation, and prosperity it has always been. Good enough as an argument except for the reality that Internet development during the last decade has taken us nowhere near to 2012 with an incredibly unbalanced digital ecosystem. A few numbers of almighty tech giants recap most of the value, riding on unprecedented levels of concentration, self-preferencing practices and business models based on the massive collection of data from end users for profiling and advertising purposes.” No matter how much telcos try to spin it, the fact is that the debate is fundamentally the same. Back in 2013, EU telcos suggested that “that the revised ITRs should acknowledge the challenges of the new Internet economy and the principles that fair compensation is received for carried traffic and operators’ revenues should not be disconnected from the investment needs caused by rapid Internet traffic growth.” Fair share and fair compensation are practically the same thing. At the same time, I agree with the author about the concentration and consolidation that the market has been experiencing. There is no doubt that a few players are dominant in the services they provide and that user data is often being abused and exploited. What I disagree with is the idea that fair share contributions will fix this concentration and abuse of power (and I have not seen any convincing argument from telcos suggesting otherwise). The European Union has passed two landmark pieces of legislation to deal with these issues: the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Digital Markets Act are both designed to deal with the abuse of user data and issues competition. For sure they are not perfect and they cannot address all the issues. But, they are getting there because there are people who are testing their limits and are willing to work with European institutions to make them better. So, how exactly would paying off big telcos help advance any of these two statutes? If the problem is concentration and abuse of power, why are telcos focusing on an irrelevant policy objective instead of working with other stakeholders to strengthen the existing statutes? More importantly, as I have suggested elsewhere, a lot has changed in the Internet in the past decade but also nothing has changed. What has changed is the actors participating and an ecosystem that is growing increasingly more complex. This complexity has meant that more innovation and investment had to take place in order to ensure that the Internet continues to be resilient, affordable and efficient. Content Delivery Networks (CDNs), data centers and cloud infrastructure are only a few of the examples on innovation and investment that have taken place due to the changing nature of the Internet ecosystem. What has not changed, however, is the underlying principles, norms and ethos of the Internet. As Vint Cerf has accurately written: “The Internet was designed to allow computers of all kinds to exchange traffic with each other over an unbounded collection of inter-connected networks. The direction of the traffic was irrelevant. The point was to allow traffic to flow in either direction so the network had to support both. Not all networks of the Internet are commercial services. Many are community based, non-profit or government operated. For those that are for-profit, their typical business model is to charge a flat fee for connection to the Internet regardless of the direction of traffic flow. The cost for implementing the service is a function of capacity, not the amount of traffic sent. The connection fee is commonly higher for higher speed capacity. There is no charge for the amount of traffic sent or received, only for the capacity, because the cost is the same whether the capacity is used or not.” This idea is relevant for the Internet today, it was applicable in 2013 and even before that. “All while telecom operators in particular in Europe struggle against very dire financial and regulatory conditions in a decade long downward trend on revenues, return on capital expenditure and stock market value that threatens their future viability.” This is not the first time I have heard telcos say that their financial situation is 'dire'. I am really not sure what telcos mean by 'dire' and how 'dire is actually dire'. There are others who may have more accurate data, but here's what Telefonica was stating in November 2022: "Telefónica increases revenues across all markets and earns 706 million euros in the first quarter". And here are some other interesting data that point to billions of euros in revenue. 10 billion euros for only the third quarter of 2022 does not sound dire to me. As I have mentioned before, if the idea is to make EU telcos as big as big tech then this is a different conversation all together. But, in the end, it is just a bad policy objective. To me though, he whole essence of the post is condensed in the next few sentences. “Fair share comes anew also in a very different policy landscape. With a European Commission that is moving from naive into geopolitical including clear aspirations on strategic autonomy and recognizing the need to develop its own capabilities in the digital space, where the gap with the US and China is profound and growing. In this context fair share appears as a fresh multipurpose tool that could help to address a number of the most critical policy goals of the EU.” Frankly, I am pretty tired of this fearmongering and this ill-defined and abstract idea of digital sovereignty that is based on the idea that Europe can do it alone. This is hyperbole because, in fact, Europe cannot do it alone. No one can and, if this is the policy direction that Europe wants to take, then we all need to be prepared for a fragmented European Internet. I never considered Europe as naïve and I am surprised to read that telcos did so up until now. For the past decades, Europe has been strategic in ensuring that non-European companies entered the single market and complied with it rules. It has managed to create the conditions for European users to get connected and, to do so, in an affordable manner. It has also paved the path for all the regulatory activity we have seen in the past few years. Calling Europe naïve negates all these efforts. It is true that the geopolitical environment is very much different today. It is true that countries have the tendency to look inwards and to bounce back to protectionism as an easy solution. But, in the long term, none of this is going to ensure a globally competitive Europe; none of this is going to ensure a European Union where users enjoy affordable and reliable access to the Internet. The European Commission knows that; EU telcos know that. One final point: I am surprised to see that none of the significant consumer protection issues are not addressed in this blog. They are not addressed as part of the European Commission’s recent questionnaire. And, it is disappointing. I am a European consumer; I am a European user. And, frankly, I start to get significantly concerned with what sort of an Internet experience I will be having in Europe should the fair share plan proceed. |

|