|

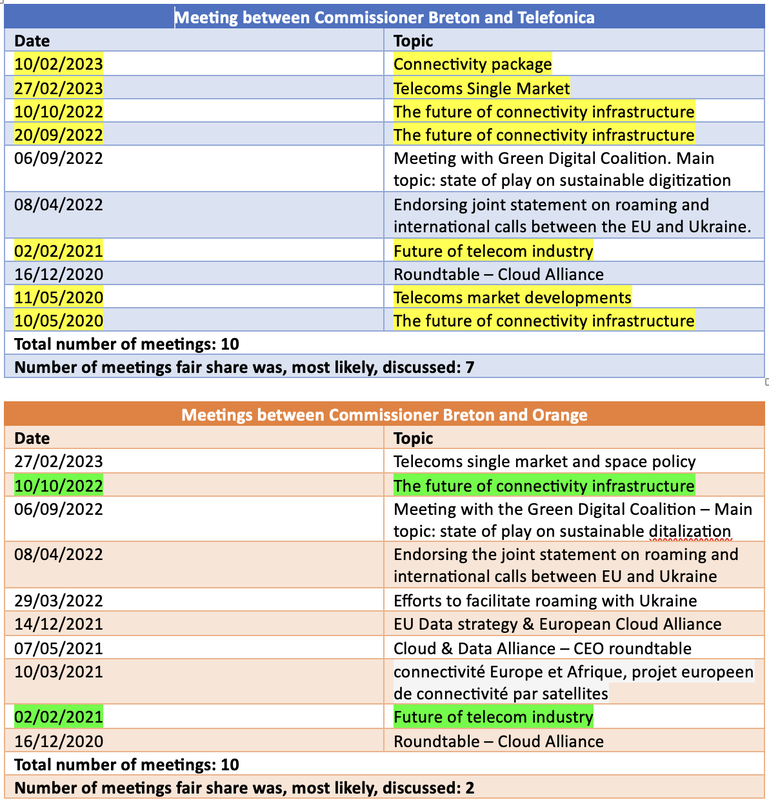

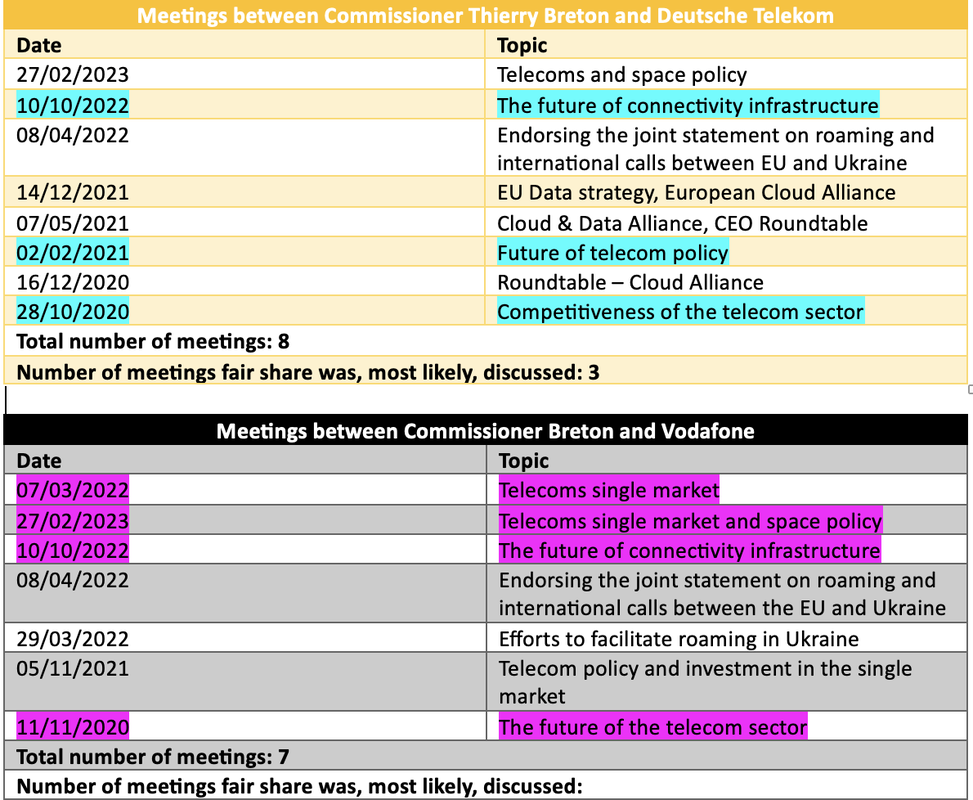

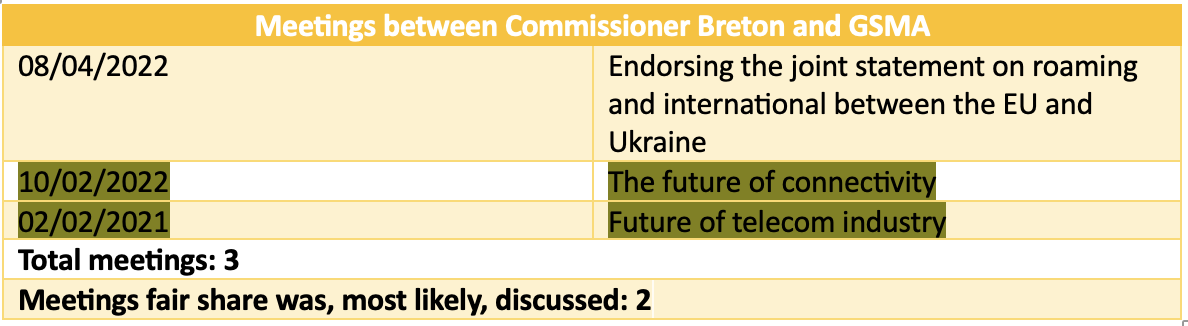

At the Telecom (TTE) Council meeting in Luxembourg on June 2nd, the fair share proposal suffered its biggest blow to date. According to Reuters, “telecoms ministers from 18 countries either rejected the proposed network fee levy on tech firms, or demanded a study into the need and impact of such a measure”. Numbers don’t lie. To have 18 of the 27 EU member states express serious reservations is indicative of the proposal's problems. And, if it was any other issue and any other Commissioner, this number would have prompted the proposal's immediate reconsideration. Not, for this Commissioner though. The issue persists in the mind of Commissioner of the Internal Market, Thierry Breton; this raises a lot of questions (and concerns). The fair share debate stopped being about facts around six months ago. As soon as it became public that the Commission’s Internal Market division is willing to reopen ETNO’s 2012 idea on network fees, an overwhelming majority of the EU’s stakeholder community chimed in with evidence about its dangers, facts about its unlikely success and concerns about its impact on the Internet and Europe. Over the course of this past year, the arguments about the way the idea of network fees will affect consumers, competition, investment and the Internet have been repeated to the point of exhaustion. Even BEREC, the body of national telecommunication regulators, has repeatedly said that there is no proof that any of this is necessary. Yet, Commissioner Breton insists on presenting a different reality. In this reality, only Deutsche Telekom, Orange, Vodafone, Telefonica and Telecom Italia – and their affiliates - are right. Commissioner Breton is also right. But everyone else is wrong. Naturally, this does not make any sense, but it does beg an interesting question: why this level of persistence? I have been asking myself this question for quite some time now. For sure, there is an element of Breton’s strong wish to boost European companies; but, the most important factor seems to be that Breton, a former telcos CEO, can’t seem to get out of the telcos' mindset. If you combine these two considerations, then the result takes the form of the toxic “fair share” proposal. Breton’s borderline obsession with this issue, despite being overpoweringly rejected, does not sit well with me and, should not sit well with any European citizen. I decided, therefore, to explore a bit the current relationship between EU telcos and Commissioner Breton. The European office of Transparency International offers a great Integrity Watch EU tool and a quick search on the meetings Breton has had in the past three years with stakeholders is quite telling about the levels of access telcos have had as opposed to civil society and other NGOs. The tables below show the number of times telcos have had meeting with the Internal market unit, to which Breton was present. In some of the meetings, all telcos were present, other meetings were bilateral. Based on the topics, it also looks that some meetings were more directly related to "fair share" than others. It is impossible from the tool to know whether other stakeholders asked for a meeting and got turned down or they did not request a meeting at all. But, in the end it does not matter: Telefonica, Orange, Vodafone and Deutsche Telekom have been meeting with Breton on quite a regular basis for the past three years, deliberating on how best to reform the telecoms sector, discussing issues of infrastructure development and without the participation of other affected parties. At the Mobile World Congress, earlier this year in Barcelona, Breton even posted a tweet about another private meeting where the "financing the infrastructure of connectivity tomorrow" was discussed. When I look at these tables and the number of meetings, it is obvious that we are talking about downstream lobbying or the “attempt to influence particular policy measures that might directly affect the industry concerned”. Of course, every company, telcos and big tech alike, engages in some form of downstream lobbying. (Unfortunately, that's how lawmaking works these days, but that's a whole different conversation.) But when downstream lobbying is combined with “cultural capture”, things are totally different. A study conducted in Quebec, Canada showed that “cultural capture” can happen “when public officers come from the same private sector now within their purview. Based on public officer’s allegiance to their former industry, lobbying is de facto exerted, “from within”.

This revolving door situation – the fact that Commissioner Breton comes from the telco sector and is now a Commissioner responsible for much of its future – can lead to regulatory capture or “the result or process by which regulation […] is consistently or repeatedly directed away from the public interest and toward the interest of the regulated industry, by the intent and action of the industry itself”. This regulatory capture becomes even more profound when associated with “cultural capture” or the idea that “those in charge of the relevant state entity [internalize], as if by osmosis, the objectives, interests and perception of reality of the vested interest they are meant to regulate”. This partly justifies the reality Breton is presenting to the world regarding the state of infrastructure investment in Europe. But it is a reality that no one seems to buy into apart from a handful of telco CEOs. And, the worst part of this reality is that the Internet’s topology is changed, consumer concerns are non-concerns and telcos are fully in charge of the way European users communicate and absorb information. It is a reality that significantly departs from the established norms of evidence-based and unbiased rule making. It is a reality that will set Europe back. In it is submission to the United Nations’ Global Digital Compact (GDC) process, the Secretary’s General’s initiative for the future of the Internet, the European Union, on behalf of its member states, writes: “The COVID-19 pandemic heightened the importance of access to secure and trustworthy digital infrastructures and technologies, underpinned by proper regulation including in the field of health. This includes the protection of users' rights online and the creation of fair, open and contestable online markets. Net neutrality is a key issue to be maintained and protected.” [emphasis added]. This level of hypocrisy is exhausting and dangerous. Hypocrisy hides the truth from people, it shields legal wrongs from public scrutiny and, ultimately, undermines the very rule of law. The Commission must kill the so-called “fair share” before it is too late. Comments are closed.

|

|